3.1.3 Publication of Financial Reports and Your Decisions and Actions

The key principle expressed in the United Nations Convention against Corruption Article 7.3 about party and campaign finance is transparency. This cannot be achieved unless received financial reports are published in a way that is accessible for average voters, and also for those who may be more likely to reach the voters – in particular media. In addition, clearly publishing information about your decisions and actions can help inform the public about your activities.

In practice, the amount of data included and the modern tools of communication used mean that there is only one form of publication of political finance data that matters, and that is online publication. Even if there is a legal requirement for financial reports or summaries of reports to be published in a specific outlet, such as in a national Gazette or similar, this does not mean that data cannot also be published on your website. Assuming that centralised, on-line publication is not specifically or explicitly prohibited, the principle of transparency means that you should use the most transparent publication approach that your resources and external factors allow, so the people have access to relevant information.

All political finance oversight institutions can (barring legal prohibitions) publish received financial reports from political parties and electoral contestants on their website. The minimum requirement is a computer and a scanner to create electronic versions of submitted hardcopy (paper) reports, plus at least a dialup internet connection. At the other end of the spectrum are systems where parties and electoral contestants submit financial reports electronically, meaning that the data is already in an electronic format and can be easily prepared for publication.

It must be stressed that the fact that your institution publishes the data received from different political parties or electoral contestants does not mean that you take responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of this data – the responsibility for any inaccuracies or omissions remains with the submitting entity. This means that data can be published before any review has taken place. Your institution may subsequently engage the reporting entity in ensuring that the published data is more accurate and complete, to increase the relevant information available to users of the data publication. In this case the focus is on ensuring the availability of financial data to the public, rather than on the review of submitted financial reports to detect inaccuracies or omissions that may entail violations of the regulations – for more on that issue, see here.

The case of Finland is particularly relevant here – in their system, the political parties upload their data in a database maintained by the oversight institution, but where this data is directly available to the public. This means (in line with Finnish legislation), that the oversight institution is not involved in the publication of data, apart from providing the system for parties to upload the data to.

These are important actions that your institution should consider regarding the publication of financial data:

- Overall planning of data publication

- Connecting reporting and publication

- Making sure that data is published in a user-friendly format

- Managing the publication of data

- Publishing information about your decisions and actions

A useful guide to the electronic publication of political finance data (in that document referred to as “disclosure”) is Digital Solutions for Political Finance Reporting and Disclosure.

3.1.3.1 Overall planning of data publication

The starting point for developing an online publication approach should be an internal discussion establishing answers to these questions;

- What is the purpose of the publication system – what goals should it achieve?

- What legal provisions are relevant for the publication system (both requirements for publication and limitations, including privacy provisions that may exist in other legislation)?

- What data (reports) should be published in this system?

- Who submits the data (reports) that should be published?

- What steps need to be taken to develop the publication system?

- What should be the process of consultation and user testing?

- What cyber security considerations are needed?

- How can the data be backed up securely?

- How can the system be made accessible to persons with disabilities?

- How can the publication system be measured and evaluated?

It can be useful to create a project plan for the online publication system, such as the one in Annex B in this document (based on the UK PEF Online).

The consultation process must include both those who will be required to submit reports that will be published (in most countries political parties and electoral contestants), and likely users of the publication system, such as civil society groups and media outlets, and possibly also academics and other public institutions. For more information about the importance of civil society and the media in raising awareness about political finance, see the section on Increasing public awareness.

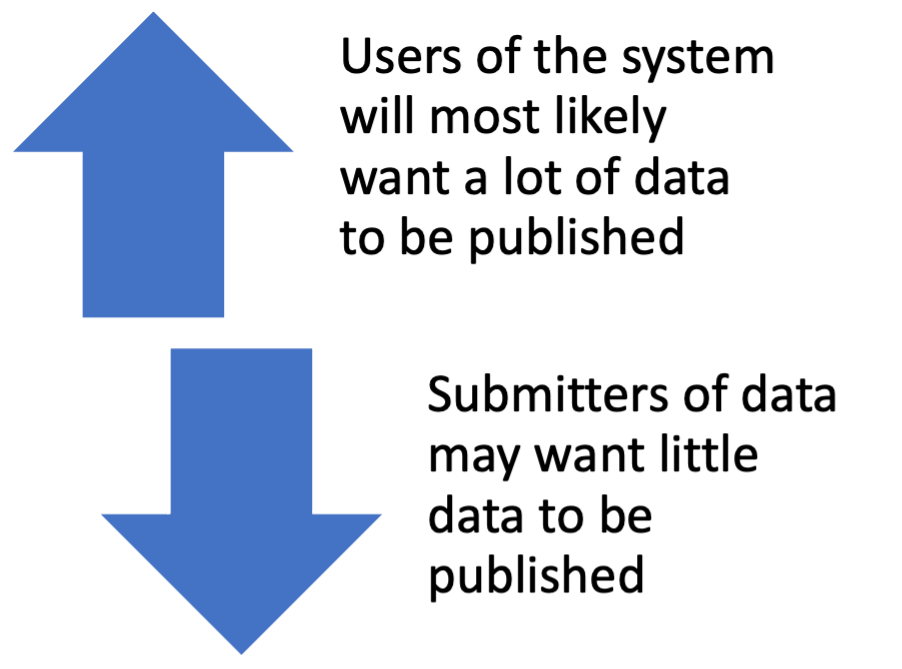

Do expect that the views and preferred solutions will vary between these stakeholders. Those required to submit financial reports are likely to wish for the system to require little work from their side, and for the data included to be limited. On the other hand, civil society groups are likely to ask for vast amounts of data that they can downloaded and analysed. Expect journalists to focus on readily available data published quickly, and where possible including ready analysis by your institution. Developing infographics and similar visually appealing messages can assist your institution in getting its message across in the media, though you need to be careful in ensuring that any analysis you provide does not lead to your institution being accused of political bias.

Academics in turn will be less focused on data being available quickly, but are likely to request access to raw data that has been submitted. They will benefit from the data being available for download in a user-friendly format.

In general, you should be ambitious and focus on a high level of transparency, but it is also important to be realistic. Remember that the system you develop must be sustainable. If the system is being developed with assistance from international actors, consider how it can be maintained when such assistance may no longer be available.

Most persons working for oversight institutions are not IT experts, and it is recommended that IT expertise is brought in at an early stage to ensure that the envisaged system is possible to create in practice with existing resources. Persons with expertise in ensuring that systems are accessible to person with disabilities (often disability advocates) should also be brought in to provide input on how the publication system be made accessible to all. Whoever is brought in to assist with the system, you must make sure that you always retain ownership of the development process and the final output.

You should also consider what legal or other limitations that may exist regarding the publication of submitted financial data. This can relate to privacy concerns, such as publishing the addresses or ID numbers of donors (the Swedish law on political finance oversight allows publishing the identity of legal entities making donations, but for privacy reasons bans publishing online the identity of private individuals making donations). Limitations on publication can also relate to thresholds of donations – the law may for example say that the identity of donors can only be published if they have donated more than a certain amount during a given period. In such cases, you must ensure that you have a system allowing you to sum up the total value given by the same donor (this will be easy if your data includes unique ID numbers, but very complicated if you for example have the name of donors, and there are many people with the same name). A particular situation exists in South Africa, where a donor can formally request that personal information is not published. The Commission must then decide whether to agree to this request, taking into account among other things "the public interest in disclosing the information in question and whether it outweighs [the need for anonymity]" (Article 2 in the Political Parties Funding Act Regulation 2021).

3.1.3.2 Connecting reporting and publication, and preparing data for publication

Naturally, one factor influencing how you can publish received financial reports is how these reports are provided to you. If they are provided in hardcopy (paper) format, especially if the reports are filled in by hand, then you will have to act differently than if the reports can be done through entries on your website, or through the submission of electronic files.

If you are developing an electronic reporting system, make sure that it is designed from the beginning to allow for the data being made public without hassle (possibly without any intervention of the OI). If a system is used whereby political parties or electoral contestants send financial reports using electronic files such as Excel, have an IT expert check that the forms being developed are designed so that the data can easily be “scraped” and entered into a database. If you end up in this situation, try to ensure that those submitting reports can only enter information in the expected manner, and not alter the form in any way, since this may hinder attempts to scrape submitted data into a database. This can for example be done by protecting cells in Microsoft Excel or by using form-enabled PDF files (the latter can however be a little tricky).

Finally, remember that financial records can be entered into an electronic database even if they are submitted to your institution in hardcopy (paper) format. This is most easily done through having staff of your institution, people borrowed from other institutions, temporary hires or even volunteers manually enter data from paper submissions into a database. These individuals should only require basic training, and need have only basic computer skills. If you are worried that people may intentionally or unintentionally make mistakes in entering data, a system can be set up where the same data must be manually entered by two different people, and have the system set up so that it rejects any cases where the entries do not match. While manual entry will certainly require some effort, a great advantage apart from being able to publish the information in an easily accessible format is that this will also greatly assist your review of received reports, including cross-checking the data with other data sources.

If nothing else works, with a simple computer and a scanner you can create electronic versions of any received files. If these have been filled in with a computer originally, it may even be possible to scrape data from these electronic files and enter into a database automatically (seek advice from an IT expert on how this could be done). On the other hand, if the reports have been entered by a political party or an electoral contestant using a computer, you should ask yourself why you do not have access to that electronic file, instead of a printout or a PDF file.

In some countries, legislation requires that reports are signed by hand, which may require the submission of hardcopy (paper) reports, even where these have been filled in using a computer. In such situations, it may be possible to reach an agreement with those required to submit reports that they fulfil the legal requirements by submitting a signed hardcopy of reports, but at the same time voluntarily submit the information in electronic format. In practice, this can mean that they fill in a Microsoft Excel reporting form provided by the oversight institution, and then both print, sign and send a hardcopy (paper) version of the report, and email the same file to the oversight institution.

A final word – as discussed in the section on advisory services and the section on preparing reporting, it is essential that you provide careful guidance to political parties and electoral contestants on how to submit their financial reports. If they do not submit their reports accurately, you will not have data to publish (or at least not have the data in the expected format).

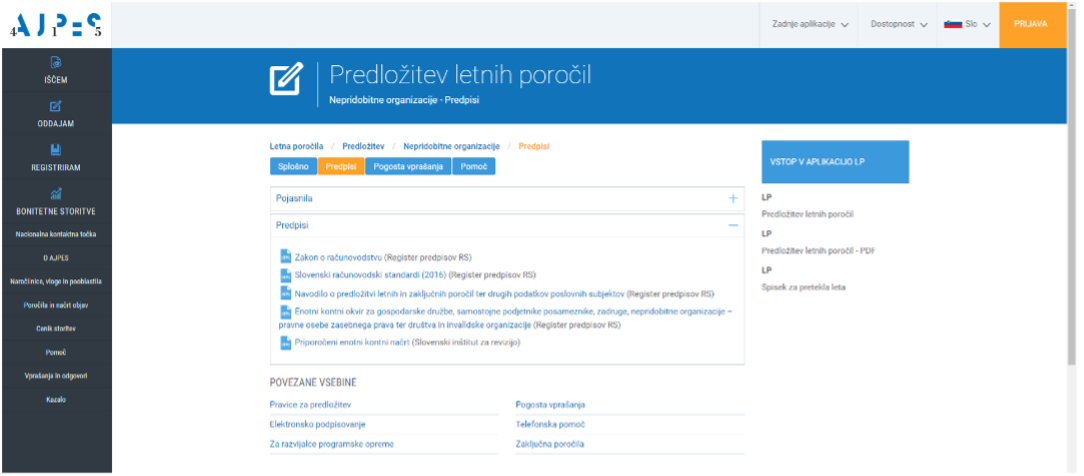

Here are some examples of guidance materials specifically provided for electronic reporting;

Australia – Guidance on submitting financial reports using the eReturns system

Bosnia and Herzegovina – User Guide for Submission of Financial Statements Using the Application “FI CIK BiH”

Brazil - Frequently Asked Questions regarding the Annual Accounts Rendering System

Croatia – “Guide to Regular Annual Financing of Political Parties, Independent Members and Independent Councilors” (includes a quiz for users to test their knowledge)

France – Guidance provided for the 2021 elections

3.1.3.3 Making sure that data is published in a user-friendly format

Data received about the financing of political parties and election campaigning should be published in an open and accessible format. Consider the Open Data Charter, which expresses the need for data to be open, timely, accessible and comparable.

There is no technical agreement on how to publish political finance data in a user-friendly manner, and the best approach in each country depends on the data being submitted, on resources available, and of course on existing legislation and regulations.

Your institution should seek to publish the data so that it allows users to as much as possible access the information that they are interested in. Ideally, the database should allow users to search over all submitting entities and years/elections. For example, has John Doe made a donation to any political party at any time (allowing for searches across reports submitted by different political parties and election contestants over the years)?

If you have data from earlier years/elections, consider how these can be made available to increase the information available to the public. Start with publishing the newest data available when the online publication system is created, since that is what users will be most interested in. Then go backwards in time and add older reports. Be aware that adding older reports to the publication system may be more complicated and demanding as systems and definitions may have changed over time. See further in the section on managing the publication of data.

Information from received financial reports can be published in static tables or graphs. Such an approach can be very valuable for journalists and others interested in getting an immediate overview of the data. However, note that such tables do not themselves make it possible for users to explore the provided data.

An important issue if you are publishing graphs and summaries of data is the extent that a public institution can go in analysing received data before their neutrality of the institution may become questioned. It would, for example, not be a problem to report how much of the total party income that parliamentary parties receive from public funding on average. However, if your institution emphasises how much each individual party received from, for example, property developers, it is possible that accusations of bias may be made, and the same could happen if you publish that a certain party received 90% of private donations from only ten donors.

If you are publishing a database with the of received financial reports, make sure that data can be downloaded. One of the most common approach for the publication of databases is through Comma-Separated Values (CSV), which is in effect a simple text file where the information (columns) are separated by commas (hence the name). Note that if the comma (",") is a commonly used symbol in financial records in your country (either to separate thousands or as a decimal comma), exporting data using CSV format may lead to the data being inaccurately displayed. In such cases, depending on the structure of your data, you may wish to consider using a Tab-Separated Values (TSV) system.

If you using CSV to publish the information, make sure it is possible to understand the data once a user has downloaded it, as there is a risk that CSV data comes out in a very confusing manner, even when users can modify the files through software such as Microsoft Excel (the Swedish system for example has limitations, while a more user-friendly approach is used in the UK). The Electoral Commission of South Africa allows users to download a summary of reports in xls format (in the third quarter of 2021, South African political parties together reported having received 39 donations).

Political finance data and the regulations that control them can be very difficult to understand for those who are not accountants/auditors or financial/legal experts. Make sure that complicated terms and concepts are clearly defined and explained whenever possible. Also consider the users when preparing these explanations - it may not be possible to explain very complicated concepts to average citizens, so you may wish to consider having several levels of explanations of key concepts, with basic information for casual users, and more detailed explanations for users willing to spend more time on the information. Do however also consider the implications that such an approach may have on the workload of your staff.

Also make sure that the publication system that you use is accessible to your users. This can include translating certain data into different languages, as well as accessibility for persons with disabilities.

There are many approaches that can be used to ensure that users can access the submitted data in different formats. The National Agency for Corruption Prevention in Ukraine has published an Application Programming Interface (API) which allows those with a significant interest to develop applications through which the data can be made publicly available in different formats.

For examples of databases by public oversight institutions, please click on the name of the respective oversight institution in the table below.

3.1.3.4. Managing the publication of data

In this section we consider some practical considerations for the planning, original publication and maintenance of received financial reports.

As mentioned earlier, the system must be based on careful planning, consultation with internal and external stakeholders and field testing.

One issue to consider is the likely workload for the uploading and maintenance of the publication system. You will need to ensure that you have the necessary personnel available, noting as well that the times of financial reporting deadlines tend to also be times when oversight institutions have an especially high workload also in terms of the review of the same reports, as well as in terms of stakeholder engagement. This can put special demands on staff recruitment, and you may need to bring in additional staff or hire outside IT support. Naturally, the more automated the system is, the less staff workload you should expect from the system (assuming that it works). A system where you may need staff or volunteers to manually enter data received in hardcopy (paper) format into a database will most likely be significantly more demanding. Manually scanning paper documents for publication on your website as PDFs is less demanding, but may still require a significant temporary increase of personnel for the data to be made public quickly.

Cyber security considerations are very important for your publication system of received financial reports. Cyber security should be considered at every stage of the process. This should begin by establishing an understanding of the types of data and the sensitivity of that data while designing system requirements and continue through making sure security requirements are reflected in procurement tenders and adequately addressed by vendor bids. Security is important to consider across the system's life cycle and is a central part of maintenance (for example, making sure security updates are continuously applied). Finally cyber security extends to making sure system components are disposed of properly with all sensitive data either removed or destroyed after a system is decommissioned. Additional consideration should be given to the design of systems that will interact with public facing components, the interface between the public facing portion of a system and the private "back-end" needs to be engineered to integrate protections against unauthorized access and be resilient to attacks against the system's availability among many other considerations. Bringing in IT and cyber security experts at an early stage can significantly assist in reducing the likelihood of problematic security concerns that can hinder system efficacy and expose the system to unnecessary risk later in the process or after commissioning. The system will need to also be integrated into larger cyber security incident response plans, which will need to be updated to account for new procedures to return to operation after interruption due to cyber-attacks or other problems.

Many oversight institutions will have an accumulation of received financial reports going back several years and several rounds of elections. You should consider how these reports can be made available to the public in a user-friendly format. When an electronic publication system is set up, focus first on ensuring that the current reporting system is suited to how the data will be published. If you have a lot of old reports, review these to see how the system can most easily also accommodate the migration of this data older to the new publication system (even if the data has been previously published for example as scanned PDFs). Do not wait with launching you online publication system however until you have migrated older files - make your system available to the public as soon as the most recently reported data has been imported. If it is not possible to add older data into a system being developed for future reports, you can consider adding an "archive" where the older data is provided in its existing format.

The final but one of the most important considerations to stress is the need to test the system, at all stages of its development and from various perspectives. You will need to test the cyber-security of the system, as well as how well it manages large amounts of traffic without breaking down (stress testing). Perhaps most important is testing by potential users who have not been involved in the development of the publication system. It is very easy when you develop any system that you come to take for granted that what you develop will be understandable for all users. However, these assumptions may be incorrect, and it is very useful to have persons from different categories of potential users (average citizens, journalists, CSO activists, academics and even staff who have not been involved in system development for example) test out the system before it is officially launched. Younger people tend to be more used to advanced technological systems, so make sure that your test panel includes person of all ages.

See more about developing a political finance publication system through a user experience design on page 36 in this document.

3.1.3.5. Publication of your decisions and actions

Publishing received financial reports is essential for increasing transparency in political party and campaign finance, and for using the public to support controlling the accuracy of the reports.

To fully show that your institution is active in overseeing compliance with political finance regulations, and that your institution is itself transparent about its work, you should also seriously consider how to publish information about your activities and decisions.

Annual activity reports can be useful (see here for the once published by the oversight institution in France, though it is strongly advised that your institution also publishes information on an ongoing basis.

Regarding your activities, it is important that you clearly show that you have provided guidance to political parties, candidates and others on how they should comply with existing regulations. This means that every time you hold a training for party treasurers or publish a guidance manual for candidates, you should make sure that this is visible on your website. Doing this not only shows the public that your institution is taking its mandate seriously - it is also useful for ensuring that people realise that the responsibility for parties and candidates failing to comply with regulations lies squarely with them, as your institution has done all it can to assist their compliance.

In addition, you should also publish information about all engagement you have with other stakeholders, including coordination meetings with other public institutions and information exchange with civil society groups, see further here. You may not always want to disclose the details of what was discussed or agreed, but at least you can publish information that such meetings were held, again helping to increase public confidence in your institution and its work.

Finally, it is important that you publish information about decisions that your institution has taken that relate to political finance. This would include decisions that relate directly to what political parties and electoral contestants need to do to comply with existing regulations, as well as decisions that relate to the oversight of political finance regulations. The publication of your decisions lets the public know that you are taking an active role in giving life to the political finance regulations in your country, and it lets stakeholders know in a timely manner what is required of them.

For example, the Anti-Corruption Agency of Montenegro publishes its decisions relating to political finance, and the State Commission for the Prevention of Corruption in North Macedonia also publishes its decisions (also on other areas of its mandate) here. Another example is the Central Election Commission of Lithuania.

Naturally, publishing decisions on the website of your institution may not be sufficient in ensuring that the information is received by all relevant institutions. You may wish to complement this by sending the decisions directly to the concerned political parties, candidates and other stakeholders.