3.3 Handling Issues of Non-Compliance

Even when you, as an oversight institution, provide exemplary advisory services, there will be times when the rules might be broken.

The nature of the rules and the mechanisms for dealing with rule breaking vary from country to country depending on whether the law provides for criminal or administrative approaches (or both) and whether you have the power to conduct both administrative and criminal investigations, impose civil sanctions and/or bring criminal prosecutions. In some countries, the political finance oversight institution must pass criminal matters to the police for investigation and the courts to take action.

In a criminal regime, breaking the rules normally leads to 'offences'. There are many terms for non-criminal rule breaking depending on the country and the regime, for example 'violation', 'breach', 'non-compliance', and more. We will use the term 'breach'.

It is essential that any oversight regime includes methods by which potential breaches of the rules can be pursued and action taken, where appropriate. Without a robust mechanism to deal with breaches, there is little incentive to comply, and no deterrent to those who wish not to do so.

Whatever the regime, the mechanism generally has two elements:

- Investigation - Steps taken to establish to the required level of proof whether a breach has occurred; and

- Enforcement - Deciding and implementing the action to be taken where a breach has occurred

You must have in place policies and procedures to ensure that the steps you take in pursuing and actioning possible breaches are, and are seen to be, impartial and consistent. This is not just to ensure individual cases are successfully handled but to protect the legitimacy of the entire oversight body, because public trust will be undermined if there is a credible suspicion that you are not completely impartial.

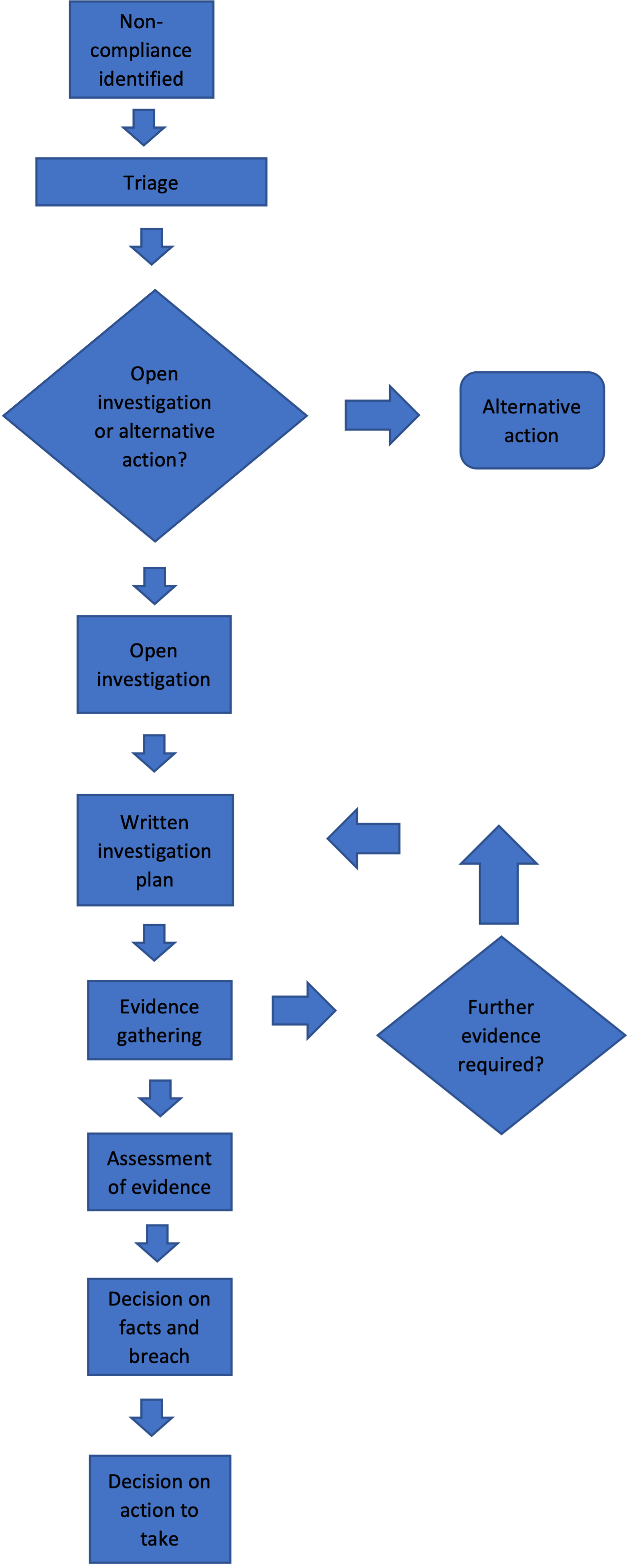

Handling breaches can be broken down into distinct stages:

- Triage – Deciding whether to investigate a matter

- Investigation planning

- Gathering evidence

- Record of evidence

- Assessment of evidence obtained

- Reaching conclusions on the facts

- Decision on whether a breach has occurred

- Decision on action to be taken

Here is a flowchart showing how these stages can work:

The two elements of investigation and enforcement action should be separated as far as possible if you do both. Different parts of the organisation, or different people, should independently decide whether a breach has occurred, and what action to take when it does. This separation of decision-making is not always a legal requirement, but it helps avoid suggestions that the final decisions were unduly influenced by the views of the investigator(s) and is in keeping with the general legal principle that one cannot be both judge and jury. There should be some formal avenue for the person/entity being investigated to have the opportunity to challenge the evidence and recommendation of the investigators and present their own evidence and arguments to the decisionmaker. This can be done on paper or in a formal hearing. It is highly recommended, especially in countries where investigations and sanctioning decisions are not undertaken by different individuals, that there are clear rights of appeal, either to a higher level official or to the court.