Ch. 1: Introduction

Alternative Dispute Resolution in Elections

Introduction

Misunderstandings, tensions, and disputes among candidates, political parties, and their supporters can arise not only on Election Day and when results are announced, but also during the pre-election period.1 One candidate may allege an opposing candidate violated the campaign rules, or a party member may allege intimidation of a group of voters by another party. As elections are a fundamentally competitive process, disputes are to be expected. However, if they are not properly addressed, political tensions can escalate. Some disputes may have roots in longstanding societal conflicts and divisions that pre-date—but manifest during—the electoral process. Sometimes election violations such as destruction of campaign materials, disturbance at political rallies, on- and offline hate speech, and abuse of state resources by incumbent candidates can remain unaddressed until well after the elections are over (if they are addressed at all).

Delays in sanctioning violations or adjudicating legitimate grievances can be due to the constraints of the electoral timetable, limited resources for law enforcement and the judiciary, or the inadequate jurisdiction or power of the conventional election dispute resolution (EDR) bodies. While conventional—or formal—adjudication mechanisms are vital to upholding the rule of law and protecting fundamental rights, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes, such as mediation and conciliation, may be useful to ensure disputes do not escalate into conflict before or on Election Day. In particular, ADR can be useful in fragile and post-conflict states; in new democracies where election disputes must be resolved quickly to avoid violence; or where “the legacy of decades of tyranny, dictatorship, absence of the rule of law, abuse of human rights, and war can lead to a fundamental mistrust of the legal system by citizens.”2

"ADR refers to a range of approaches—from negotiation to mediation, to fact-finding mechanisms, to semi-private decision-making forums such as binding arbitration—that are intended to help parties reach agreements. They supplement and enhance a country's formal judicial processes by providing an alternative avenue for parties to resolve their disputes."

- IFES, Guidelines for Understanding, Adjudicating, and Resolving Disputes in Elections (GUARDE)

If used appropriately, ADR provides several advantages over conventional EDR mechanisms, including resolving disputes more quickly and at a lower cost than the court system. ADR can engender more local access to justice, offer more targeted remedies, and strengthen dialogue at the community level.

This can build confidence among members of the community and improve the legitimacy of the electoral process by involving stakeholders more closely in the dispute resolution process. Recent global surveys have illustrated the lack of trust in government institutions and the decline in democratic values, particularly among young people.3 In this context, ADR can play an important role by providing a more inclusive, multi-actor forum to resolve electoral disputes. While ADR bodies are primarily led by election officials, civil society organizations (CSOs), political party representatives, and community leaders are often members and can actively participate in reaching a settlement or resolution to the dispute.

ADR’s informal structure can enable simpler implementation at the local level, allowing for the involvement of non-traditional actors both as mediators/arbiters and as disputants. This creates a system that is more accessible for grassroots political parties, local candidates, and individuals to seek remedies and obtain justice. ADR can also enhance the participation of women or traditionally disadvantaged or marginalized groups, both as petitioners and as adjudicators/mediators; its flexible approach is often more welcoming and user-friendly for individuals who are unfamiliar with formal judicial proceedings or have limited physical or financial access to the judiciary. For example, in Mexico, the Election Institute of the State of Oaxaca has introduced mediation as a means of resolving disputes in Indigenous communities that elect their local authorities using traditional practices. In India and Sri Lanka, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) has supported projects to increase the participation of women in Muslim community Qadi courts as users and arbiters. This is a way to support Indigenous traditions and find inclusive, consensual, and culturally appropriate ways of resolving disputes, as well as reducing pressure on over-burdened electoral tribunals.4

Despite the advantages it offers, ADR remains underutilized in elections or, in some cases where it is utilized, it is not optimally designed and implemented. There are also risks to the introduction of ADR in elections, including if the mechanism lacks sufficient details in the legal framework and guidelines on the mandate, responsibilities, and procedures for ADR; adequate resources to train election officials or other involved actors on ADR skills such as mediation, conciliation, or arbitration; and sufficient stakeholder awareness of the ADR mechanism.

Legal practitioners and anti-corruption experts have flagged challenges regarding the use of informal and customary dispute resolution systems outside the electoral context in various countries. A report by the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre explained this conundrum as follows: “On the one hand, such systems tend to be far more affordable, comprehensible, and accessible to the poor than formal state justice systems. On the other hand, just like formal justice systems, informal systems may feature corrupt and otherwise unfair influences and biases that produce unjust outcomes and perpetuate inequities.”5 Jan Beagle, Director-General of the International Development Law Organization, has noted that it is important to “engage with the system that most people turn to,” and “recognize legitimacy of these [informal justice] systems.” But she also flagged the need to engage strategically with these systems to ensure greater respect for human rights.6

From the text:

In 2011, with USAID support, IFES published Guidelines for Understanding, Adjudicating, and Resolving Disputes in Elections (also known as GUARDE).7 These guidelines included a chapter on ADR—including mediation and conciliation—in election disputes, based on preliminary research on the emerging use of ADR. Ten years later, the growing implementation of ADR in election disputes has provided new insights into good practices identified in GUARDE and also highlighted some challenges to the use of ADR.

In South Africa, the Electoral Commission (IEC) was one of the first election management bodies (EMBs) to introduce and utilize these modes of dispute resolution. The IEC created conflict management mediation panels in local communities to mediate election disputes and deter electoral violations as the country sought to establish the credibility of its post-apartheid democracy.8 While election officials chaired these panels, party representatives and members of the community took part in encouraging peaceful settlement of the disputes. This model has inspired other countries in Africa: Zambia, Malawi, and Nigeria have rolled out mediation initiatives by their election commissions, and in Nigeria, there is a growing push for ADR to expand to the judicial system to reduce the backlog of cases filed during the elections.9 Prior to the 2015 and 2020 elections, the Myanmar Union Election Commission instituted election mediation committees to mediate disputes arising from the code of conduct and campaign in order to address the lack of timely mechanisms to deal with disputes during the pre-election period.10

"Due to the informal nature of ADR mechanisms, EMBs have rarely collected data on the type and number of disputes handled by ADR, creating a challenge for research but also a missed opportunity to draw on lessons learned, promote successful initiatives and build trust in the EMBs' capacity to address legitimate disputes."

- IFES Guidelines for Understanding, Adjudicating, and Resolving Disputes in Elections (GUARDE)

ADR mechanisms can also increasingly be found in other parts of the world. However, little information on the use of ADR in electoral or political processes has been collected and publicized in the last 10 years since GUARDE was published.

In addition, election observers do not systematically include ADR mechanisms within their observation methodologies, although some observer missions assess them on an ad hoc basis. As a result, although interviews with practitioners and former and current election officials conducted by IFES for the purpose of this paper provided a good deal of fruitful information, there is a clear lack of systematic data on ADR across electoral cycles. It is particularly difficult to find information about successful uses of ADR. One hypothesis is that the successful resolution of disputes is marked by the absence of violence, threats, intimidation, or other illegal campaign activities. This makes it hard to assess what further conflict might have occurred had the disputes not been resolved, and therefore difficult to measure success. Nonetheless, systematic monitoring of ADR mechanisms and their outcomes would produce valuable insights.

The popularity of ADR is not unique to election disputes. In 2019, the International Development Law Organization reported that “Recurring estimates suggest non-state actors, including customary, traditional and religious leaders, address 80 to 90 percent of legal disputes in developing, fragile and post-conflict states.”11 Several organizations have produced guidelines and toolkits on mediation practices and

ADR, although they are not specific to elections.12 While research and technical assistance in election disputes have primarily focused on formal EDR processes, it is important to analyze how informal justice mechanisms operate and how they interact with the formal justice process during an election. A better understanding of these processes will help all stakeholders engage effectively with customary and informal justice, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 16 on access to justice for all.13

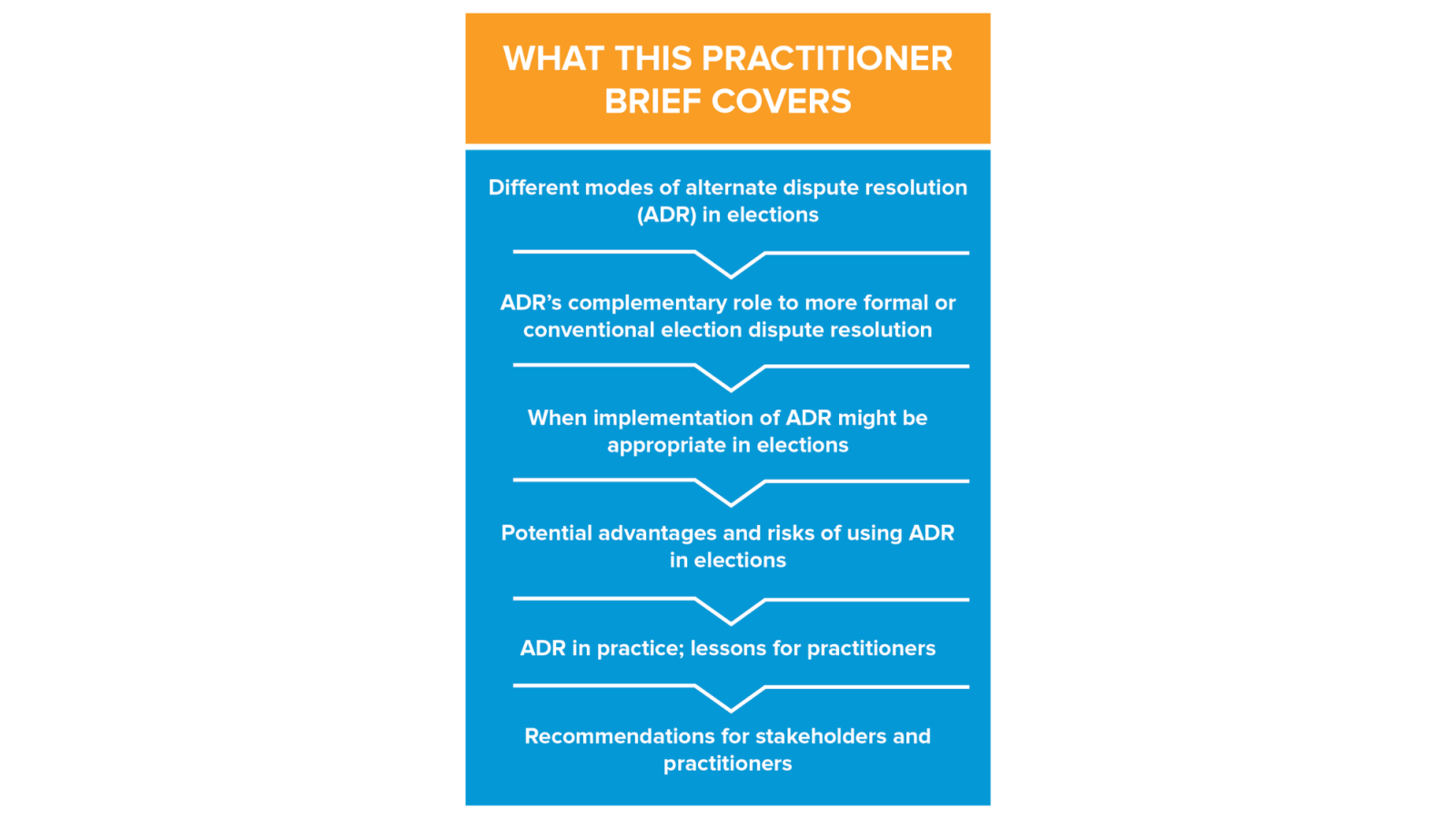

This Practitioner Brief attempts to make an initial contribution to filling the research gap on the use of ADR mechanisms in elections. It draws on lessons learned from ADR programs globally, collected through desk review and a series of key informant interviews with election practitioners, EMB members and officials, judges, experts, and local partners around the world. IFES also collected lessons learned during an in-depth consultation session with judges from the Africa Electoral Jurisprudence Network in July 2022 and secured peer reviews from experienced practitioners at Bawaslu in Indonesia and the Malawi Election Commission.

IFES is thankful for the contribution of election practitioners, EMB members, and judges, who contributed to the development and review of these case studies on the use of ADR in elections.

Purpose and Scope of this Paper

ADR has considerable potential for helping resolve disputes and enhance trust in the electoral process, yet information is scarce on how it can be used most effectively. This gap prompted the development of this practitioner brief.

EDR encompasses the range of complaints, disputes, violations, and offenses that can occur throughout the electoral cycle, including post-election cases that challenge the results of elections. However, this paper focuses specifically on ADR mechanisms for pre-election and Election Day disputes. Our research and consultations with arbiters and judges confirm that most ADR mechanisms are focused on voter registration, candidate nomination, intra- or inter-party disputes, and campaigns up to and including Election Day. In most countries, the legal framework clearly defines the jurisdiction of a court of law to address post-election results disputes within prescribed deadlines. It is important that these cases be addressed by a court of law in a timely manner, rather than through a conciliation or mediation process, as a clear winner must be determined. Occasionally, election results disputes can escalate into political crises and risk serious violence, where international or regional mediation may occur post-election. Some jurisdictions may even exclude the use of mediation for post-election disputes when specific, tight adjudication deadlines are prescribed.14 During a consultation session led by IFES in the margins of the Africa Electoral Jurisprudence Network in July 2022, an electoral judge from Malawi shared that “For post-election, ADR comes as a difficult enterprise in Malawi under the civil procedure rules limiting the practice of mediation, but (…) for pre-election disputes, it should be highly encouraged.” If the formal justice system fails, international mediation or extraordinary ADR mechanisms can be helpful to resolve the conflict, but this remains exceptional. Disputes relating to election results have therefore been excluded from the scope of this paper.15

This paper also does not assess administrative adjudication by an EMB or another body in a quasi-judicial capacity, as such mechanisms are usually set out in the law as mandatory and binding processes rather than voluntary and, as such, are considered to be conventional EDR.16 The focus of this paper is on the implementation of ADR mechanisms that aim to reach voluntary agreements to resolve disputes between different stakeholders during the election, often with the assistance of a third party. We focused our research primarily on ADR mechanisms led or coordinated by EMBs, which can include mediation committees and conflict management committees. We also have not covered every consultative or conciliatory forum set up during elections to engage in dialogue with stakeholders. Internal party dispute mechanisms or ADR led by political parties without the involvement of the EMB are outside the scope of this paper, as are the many efforts to prevent electoral violence that are led by CSOs.17

"Because EMBs play a pivotal role throughout the cycle of the election process, their institutional capacity to develop and maintain effective strategies for dispute management is essential to the consolidation of democracy and mitigation of political conflicts."

- West Africa Network for Peacebuilding

Finally, during our research, we found only limited judicial initiatives for mediation in electoral disputes—in Kenya and Senegal—and have noted some calls for judicial mediation in Nigeria, along with keen interest from some interviewees. The development of non-judicial alternatives to litigation, lack of awareness, and reluctance from lawyers can explain the limited use of ADR by the judiciary in election disputes. However, there is also insufficient research in the field due to the informal nature of these bodies, the lack of instruction on reporting, and the short time available prior to an election,19 and this is an area ripe for further study.

Summary Recommendations

The summary recommendations that follow focus on the different bodies or groups that may have a stake or a role (or both) in the effective implementation of ADR in elections. Ideally, these recommendations should be considered from the outset in the design of any ADR mechanism. However, our research also highlights the need for customized solutions based on a country’s experience with ADR, notably the culture and legal tradition of the country and the experiences and practices of marginalized communities. Given the focus of this report, these recommendations mainly focus on EMB-led ADR processes. Subsequent research is needed on judiciary-led ADR or other forms of ADR in the electoral process.

- Conduct a feasibility study and consult with stakeholders to carefully design an ADR mechanism that is suited for the relevant context, the legal tradition and culture, and the phase of the electoral process.

- Well in advance of the election process, develop clear rules on the composition of ADR bodies, the mandate of such bodies, and the consistent procedures they will follow.

- Conduct training for the members of ADR bodies and an informational campaign for key stakeholders who will be utilizing ADR mechanisms (party representatives or candidates). Consider the use of digital tools to address the potential late selection of members of mediation bodies and the limited time available for training prior to an election.

- Conduct outreach or develop educational tools for stakeholders, including the media and voters, on the mandate, role, and procedures of ADR bodies, with a focus on clarifying the distinction between ADR and EDR as avenues of redress.

- Encourage the participation of women, youth, and marginalized groups such as persons with disabilities; ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities; and Indigenous Peoples when selecting members of the ADR bodies.

- Engage with the judiciary, notably election judges, well before an election to inform them about existing ADR mechanism(s) that may be used prior to the filing of a dispute before the court.

- Set up a reporting system for disputes handled by the ADR body to enhance consistency in the process and outcomes, facilitate transparency, and increase public understanding.

- Collect and analyze data on ADR cases and conduct lessons-learned activities on the role of ADR after each electoral cycle to ensure it is being implemented effectively. Release the data to the media and the public.

- Consider a range of diverse identities, including gender, Indigenous identity, ethnicity, and disability, to promote inclusive and equitable representation of members on ADR bodies and to ensure these bodies have a gender equality policy and gender-sensitive training, as well as broader inclusion and human rights training, and that their proceedings are accessible to persons with disabilities and people with varying levels of literacy and education.

- Consider cooperating with other conflict prevention and resolution efforts for mutual reinforcement, to identify skilled mediators or conciliators at the local community level, refer potential disputes to relevant mechanisms, and raise awareness on the availability of these mechanisms.

- Provide training for judges to inform them about the formal EDR and informal ADR processes established by the EMB during the elections and how they interact during elections or may impact court proceedings during the pre-election period.

- Consider introducing tested forms of judicial ADR with specific deadlines for certain types of pre-election disputes, depending on legal tradition and practices—in particular, for intra- or inter-party disputes.

- Establish channels to request information from the EMB/ADR body on the ADR process or to refer to EMB-led mediation when relevant for a dispute or appeal in court.

- Consider introducing the use of ADR in the legal framework as a non-mandatory option for dispute resolution, or institutionalize in the law the existing practice of ADR by further defining the mode of resolution, mandate, and responsibilities.

- Adopt clear provisions regarding the exhaustion of remedies or initiatives to mediate a dispute to avoid issues of jurisdiction.

- Consider specific deadlines for mediation efforts in pre-election disputes to avoid disrupting election operations prior to Election Day.

- In cooperation with the EMB, carry out awareness raising in local communities on ADR mechanisms for elections and how it differs from formal EDR avenues of redress.

- Promote ADR as a conflict resolution and violence prevention mechanism in peacebuilding initiatives around the electoral cycle.

- Observe ADR sessions, collect and analyze data on ADR mechanisms to assess their effectiveness, and contribute to lessons learned exercises.

- Where appropriate to the model of ADR in use, participate as members of the ADR body or advocate for inclusion of youth, women, minorities, Indigenous peoples, and persons with disabilities in mediator appointments.

- Include the monitoring of ADR bodies and processes in the election observation methodology, based on pre-determined criteria and international standards, including with respect to the accessibility and inclusiveness of the ADR mechanism.

- Participate in ADR briefings by the EMB or relevant EDR/ADR body.

- When relevant, appoint a member of the ADR mechanism in a timely manner and ensure participation in trainings. Ensure representation of youth, women, minorities, Indigenous Peoples, and persons with disabilities.

- Conduct briefings for party members, candidates, and supporters on who can use the ADR process and when and how they can do so.

- Commit in good faith to attempt to resolve disputes through ADR mechanisms such as mediation or conciliation prior to filing with the formal mechanism.

- When relevant, appoint a representative in a timely manner to sit as a member of an ADR mechanism and ensure participation in trainings. Ensure representation of youth, women, minorities, Indigenous Peoples, and persons with disabilities.

- Cooperate with ADR bodies as needed (for example, in the provision of facilities for ADR training or open sessions) while ensuring that the bodies remain impartial and are not dominated by the incumbent party.

- Monitor activities of ADR bodies; attend meetings to learn more about ADR and analyze its effectiveness.

- Educate the media to clarify distinctions between formal and informal dispute resolution processes.

- Request EMB to release data on ADR mechanisms and analyze and use data in reporting.

- For conflict prevention, resolution, and peacebuilding programs: Ensure cooperation with the EMB for awareness-raising efforts around the existence of ADR mechanisms to resolve election disputes. Alternatively, identify trained mediators or conciliators in the community at the time of an election.

- For researchers: Conduct research on the effectiveness of ADR mechanisms, and collect data on the types of disputes resolved through ADR to further contribute to filling the knowledge gap in this area.

Citations

1 As well as alleged campaign violations, candidate nominations often give rise to fierce disputes, including intra-party disputes. For example: Phungula, W. (2021, November 15). ANC member who disputed the party’s candidate in Harding’s ward one silenced by gun. IOL. https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/news/kwazulu-natal/anc-member-who-disputed-the-partys-candidate-in-hardings-ward-one-silenced-by-gun-ca4fb280-42b5-4b0b-85f0-24a8e2561a13; Yang, M. (2022, January 11). Voters move to block Trump ally Madison Cawthorn from re-election. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jan/11/madison-cawthorn-trump-republican-north-carolina- voters

2 Kovick, D. & Young, J.H. (2011) Alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. In C. Vickery (Ed.), Guidelines for understanding, adjudicating, and resolving disputes in elections (GUARDE) (p. 257). IFES.

3 OECD 2021 Government at a Glance, p. 7: “Even with a boost in trust in government sparked by the pandemic in 2020, only 51% of people in OECD countries trusted their government, “[d]emocracy experienced its biggest decline since 2010” and the percentage of people living in a democracy fell to well below 50%. Democracy Index 2021, The Economist Intelligence Unit, February 2021. Foa, R.S., Klassen, A., Wenger, D., Rand, A. and M. Slade. 2020. “Youth and Satisfaction with Democracy: Reversing the Democratic Disconnect?” Cambridge, United Kingdom: Centre for the Future of Democracy, October 2020.

4 See the Mexico case study in the annex of this paper.

5 Golub, S.; (2014). Mitigating corruption in informal justice systems: NGO experiences in Bangladesh and Sierra Leone. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute. https://www.u4.no/publications/mitigating-corruption-in-informal-justice-systems-ngo-experiences-in-bangladesh-and-sierra-leone

6 Pantuliano, S. (2021, December 8). High-level dialogue on customary and informal justice and sustainable development goal (SDG)16+[Webinar]. Overseas Development Institute, https://odi.org/en/events/high-level-dialogue-on-customary-and-informal-justice-and-sdg16/

7 Vickery, C. (Ed.). (2011). Guidelines for understanding, adjudicating, and resolving disputes in elections (GUARDE). IFES. https://www.ifes.org/publications/guidelines-understanding-adjudicating-and-resolving-disputes-elections-guarde

8 See the South Africa case study in the annex of this paper.

9 See the Nigeria case study in the annex of this paper.

10 See the Myanmar case study in the annex of this paper.

11 International Development Law Organization. (2019, January 30). Practitioner brief: Engagement with customary and informal justice systems. https://www.idlo.int/publications/practitioner-brief-engagement-customary-and-informal-justice-systems

12 The Council of Europe’s European Commission for the Efficiency of the Justice Working Group on Mediation developed a Mediation Development Toolkit. The Guidelines emphasize the principles of equality, impartiality, and neutrality, and the importance of raising public awareness of the benefits of mediation.

13 Pantuliano, S. (2021, December 8). High-level dialogue on customary and informal justice and sustainable development goal 16+[Webinar]. Overseas Development Institute, https://odi.org/en/events/high-level-dialogue-on-customary-and-informal-justice-and-sdg16/

14 In Malawi, rules of civil procedure provide that in expedited proceedings like post-election disputes, mediation cannot be invoked as it could derail the speedy adjudication of disputes.

15 It is important to note that even when ADR is used, all of the legal frameworks studied either provide explicitly for a right to appeal if mediation fails or do not prevent a party from filing an appeal before a tribunal or court in parallel or after the mediation.

16 Vickery, 2011, p. 229: “In brief, ADR refers to any method that parties to a dispute might use to reach an agreement, short of formal adjudication through the courts. This can include both formal administrative law systems, in which regulatory agencies establish special rules and procedures for resolving disputes and complaints, and case-specific, ad hoc processes of negotiation and mediation, in which parties seek to reach voluntary agreements to resolve their disputes, often with the assistance of an impartial third party.” However, GUARDE makes clear on p. 238 that rather than a bright line distinction between ADR and EDR, the various approaches can be visualized on a continuum, with a greater degree of party involvement at the ADR end of the spectrum and a greater degree of time and resources spent at the EDR end of the spectrum.

17 Monitoring/tracking violence and risk factors, early warning systems, etc., are key activities to prevent disputes and can be complementary to the resolution of disputes, but are not the focus of this research as they relate more to a preventive mechanism rather than a dispute resolution mechanism.

18 West Africa Network for Peacebuilding. (2013). Election dispute management for West Africa: A training manual. p. 2. https://gppac.net/resources/election-dispute-management-west-africa-training-manual

19 European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, (2007, December 7). Guidelines for a better implementation of the existing Recommendation on alternatives to litigation between administrative authorities and private parties. https://rm.coe.int/1680747683