2.5 Performance Management

2.5.1 Overview of performance management of operations

What are performance management and performance measurement?

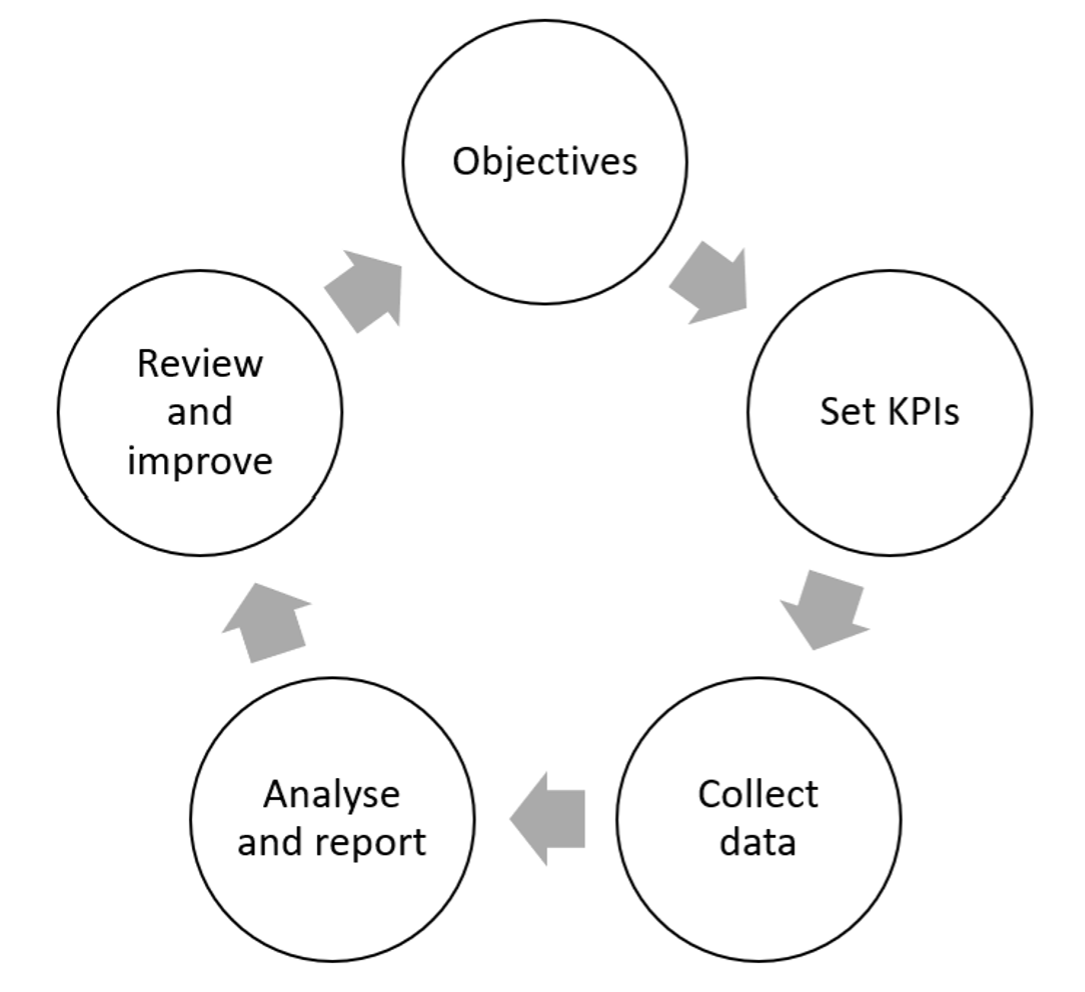

Performance measurement is the regular monitoring of metrics which an organisation has decided are useful to measure regularly. The purpose of the measures is to enable management to discern whether the delivery of objectives is progressing smoothly, and to have oversight of whether the relevant internal processes, that contribute to delivery, are functioning effectively. If any of the measures are not on track, they can then consider whether any management intervention is needed to bring about improvement and to manage performance against your set objectives, based on the performance measures.

The agreed set of performance measures (usually stored together in a document or spreadsheet) are sometimes referred to as ‘a scorecard’ or ‘a balanced scorecard’. The raw data collected from month to month is analysed and used to generate management reports.

Performance management occurs when decisions are made, actions taken (which may include a decision to continue with no change where the data indicates all is proceeding as planned), or new goals set, based on consideration of the latest performance data.

Why is doing performance management useful?

In short, what gets measured, gets improved. Monitoring and analysing performance is an important way of measuring effectiveness. It helps you to detect and understand problems and identify improvements.

Some fluctuations in performance over time are natural and inevitable. Minor fluctuations may come and go, but should still be monitored so that you notice any emerging trends. Understanding the reasons for the fluctuations can yield valuable information that leads to improvements that make performance better, or more stable. Major fluctuations will probably be obvious, with or without measurement, but armed with some proper performance data you will be able to understand what is going on more readily. Longer, slower changes over time may not be apparent at all if data has not been collected, which could mean performance slides downwards without any action being taken.

Monitoring your metrics will provide insight, flagging up when something has changed so that you can investigate why it is happening, and work out what to do to improve performance. It can also tell you if a particular measure is no longer valuable, and perhaps should be replaced.

What does performance management involve?

It involves:

- Identifying and crafting a good set of indicators that support your objectives

- Setting up a performance scorecard tracking system

- Regular measurement and recording

- Management commentary and reporting

- Regular ‘dip-checks’ to ensure that performance data is being reported by staff accurately and consistently.

Although you will want someone central to run the system and ensure that tracking, reporting and data quality checks occur, the wider organisation will need to commit to providing the raw data, and providing management explanations for fluctuations, on a regular basis. It’s important that staff contributing to the performance management system understand what they need to do, and why it’s valuable, and why accuracy and consistency are paramount.

2.5.2 Elements of performance management:

2.5.2.1 Setting Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

It’s important first to identify what is, and is not, meaningful to measure. There are many things you can measure – the question is, are they worth measuring? Will doing so tell you something valuable? And if the measure does not achieve its target, is there anything you can do about it?

For instance, counting the paperclips in your stationery cupboard will not tell you anything useful about the efficiency of your stationery ordering system. Even if there are too many, or too few, paperclips in the cupboard at the time, counting them won’t tell you whether something has gone wrong with the ordering system, or whether there are any trends in the number of paperclips available. And knowing the number of paperclips will not have any substantive effect on your ability to achieve the goals set out in your strategy.

The starting point for determining the right key performance indicators should therefore be your strategy, and not a list of ‘things you can measure’. What objectives are you trying to achieve? Your chosen KPIs should relate as directly as possible to your goals. You can find more information about KPIs both here and here.

For instance, let’s suppose you have just launched a new website with extensive guidance on the rules governing political finance and the activities you undertake. Let’s further assume that your goal is to ensure that as many people as possible are aware of the website and can find the excellent information you are providing there. You will want to know how well you are doing in working towards that goal. So you could set a key performance indicator to track your progress, with a target of achieving (say) at least 500 new home page views per month. The number of unique page views is measurable, and useful to collect. That way, when you promote the new website on social media in a given month (for example), you will be able to measure the difference between the number of page views before you publicised the website, the number of page views afterwards, and how long the positive impact of your efforts lasted. You will also be able to see when you are not achieving your target, and should do more (or do something different) to promote the website to a wider audience.

Another key indicator for political finance oversight institutions might be the percentage of annual financial reports political parties submit on time. This type of indicator serves a dual purpose. First, it ties into goal of promoting transparency of political finance. It also demonstrates that you have some responsibility for getting parties to comply with the law. Your stakeholder outreach, training and guidance efforts should help bolster a higher level of compliance with reporting requirements. If you fail to reach the key indicator of reports filed on time, then you may need to consider what improvements you can make in assisting parties to understand and meet the filing deadlines.

Other examples that might be relevant for political finance oversight institutions include:

- The speed at which data is processed, checked and published (e.g. in the context of supporting transparency by publishing information about donations or spending)

- The percentage of positive responses from stakeholder surveys (e.g. measuring whether your training helped stakeholders to understand their responsibilities, find information, or complete forms)

- The achievement of key milestones or adherence to budget for key projects (e.g. the introduction of a new system)

There will also be some functions within your organisation that are vital to the delivery of all of your objectives, regardless of what they are – for example, your finances and budget, and your workforce, without which you won’t be able to deliver anything. So you will also want to establish some KPIs around those – for instance, to monitor your balance figures and your staff turnover or sick leave.

It’s also possible to set performance measures that are future-focused, relating to the future realisation of objectives – for instance ‘By X date we will produce publication Y’. These measures function rather like the milestones you would set when planning out a project – as markers along the route from A to B. Such performance measures are sometimes referred to as ‘OKRs’, which stands for Objectives and Key Results, and would only be retained for the duration of the objective they relate to.

In comparison, KPIs are normally long-term, and relate to the quality of ongoing delivery rather than to reaching short-term objectives.

It’s perfectly permissible to have both types of measure sitting side-by-side in your scorecard.

For information about how to design effective performance metrics, see Hints and tips guide.pdf.

(to KPI template and test tool.pdf)

2.5.2.2 Types of KPIs

There are many types of KPI – the main ones are listed below to help prompt your own thoughts about what would be useful in your own organisation:

Lead indicators

A lead indicator is a measurable variable that influences your future success.

For example:

- If you wanted to get fit, a good lead indicator might be the number of hours you spend in the gym each week.

- If you wanted to make sure chief financial officers know the rules they should adhere to, a good lead indicator might be the number of CFOs attending training workshops.

- If you ran a building site, the percentage of people wearing hard hats would be a lead safety indicator.

Lead indicators can be useful if there are certain (measurable) prerequisites for success. However they are forecasts of success rather than standalone indicators of success, so should be used in balance with other indicators that measure actual outcomes. For instance, spending three hours per week in the gym won’t, on its own, guarantee that you get fitter; and neither is it the only factor in getting fit. You would need to measure your actual fitness in some way to know for sure, but spending that time in the gym certainly makes it more likely that you will become fitter overall.

Lag indicators

A lag indicator shows actual performance, after the event.

Using the examples from the paragraph above, good lag indicators might be:

- The number of minutes you can run on a treadmill, or the number of push-ups you can do in one go.

- The number of annual reports submitted by the deadline

- The number of accidents on your building site, or the number of accidents resulting in injury.

Lag indicators are generally more numerous, and easier to identify. They are a good way of measuring performance over time, and of detecting the impacts of change (for example, a new process).

Input Indicators

Input indicators relate to the resources available to you for reaching an objective. They are measures of the availability of resources, or a way of tracking the efficiency with which you are using the resources, and are especially used in large projects.

Some examples would be staff time, budget available, or the rate at which materials are being used up.

Output Indicators

Output indicators are often used to measure the delivery of products or outcomes.

Examples include financial surplus (or profits), the number of people helped, or the number of training courses delivered, or the number of leaflets distributed.

Process Indicators

Many of the KPIs we set will relate to the performance over time of a particular system or process.

For instance, how long it should take to complete a particular process from end-to-end, e.g. resolution of IT support tickets or handling of complaints.

The data collected can help to show whether any aspects of the process could be more efficient, or might require additional attention or resource. These indicators are also useful for spotting externally or internally driven changes that are impacting on your processes, so that you can address them.

2.5.2.3 KPI tracking

After agreeing what your KPIs should be, you will need to establish a system for collecting performance data.

Firstly, it’s vital that the staff who will be responsible for providing the data are given a good understanding of how it will be used and why it is important. It’s also important that any necessary training in how to source and report the correct indicator data is provided, so that you have confidence in the data supplied.

Team managers should also be involved, since they will need to provide some management commentary alongside the data, to provide context and explain the data. For instance, if you are tracking a KPI about the response time to public enquiries, and this is below target in a given month, it would be helpful to know if a particular issue that month resulted in twice the usual number of enquiries, explaining the dip in apparent performance.

You will need to provide somewhere for people to put their data. This is usually done in a spreadsheet, with one staff member taking on overall management of the spreadsheet and reporting. This performance manager can then prompt other staff to supply their data, on a monthly basis (if that is your agreed reporting frequency), and they will review the data provided and turn it into a regular management report for your senior team and/or the Board.

Ideally the person responsible for running the system should be numerate and capable of using a spreadsheet, e.g. working with formulae and performing common sense checks on the validity of data entered. It will be necessary for them to have a deep understanding of the KPIs themselves.

Periodic ‘dip-checks’ should be done, comparing the information provided with the source data for each KPI, to check that the staff reporting the data into the tracking spreadsheet have been doing so consistently, accurately, and from the correct source. Mistakes can mean misinterpreting performance, and can also be embarrassing, for instance if retrospective corrections have to be made to Board performance reports.

(Performance tracking spreadsheet.xlsx)

(Model performance report.pdf)

2.5.2.4 Management commentary and reporting

You may track as many KPIs (and OKRs if you so choose) as you wish, but it is best to try to limit the numbers. Pick those that tell you the most valuable information. A suggested limit would be 12 KPIs and 5 OKRs.

After receiving raw data from teams around the organisation, on, say, a monthly basis, a report summarising the latest performance data should be produced, for review by the senior team and/or the Board.

This report should include an executive summary highlighting key performance information, for example consideration of any indicators that are currently performing poorly (red indicators), and any new indicators or adjusted targets since the last report.

For your most important indicators, it may be useful to include a graph showing performance trends over (say) the last 6 months, alongside management commentary to explain or highlight any variations or dips in performance.

You may also sometimes need to make recommendations for actions to improve performance, since this may require changes to processes, or additional resources, and such changes may have other implications that need to be considered at senior level.