Tips for Safe, Relevant, and Inclusive Nonformal Civic Education

The data gathered from the survey and FGDs were the basis for the development of the actionable tips discussed on the following pages. These tips reflect the words and experiences of young people and provide guidance to implementers on how best to honor those experiences. Before diving into the tips, however, it is important to emphasize that practitioners should safeguard young people’s participation. Young people who took the survey and participated in the FGDs stressed this point.

When working with children and young people, it is integral to ensure that they feel secure physically, mentally, and emotionally when either delivering and participating in activities. At a minimum, practitioners should seek minor assent when engaging children and young people under age 18 in activities, as well as the permission of parents or caregivers. Minor assent—the agreement of those under age 18 to participate—provides an opportunity for children to express their agency by confirming that they understand and want to take part in an activity.

Localizing civic education and making it more relevant to young people and the environments in which they live may help to identify mechanisms and opportunities to better ensure their safety. Many respondents explained that learning occurs more organically and resonates more with them when activities are linked with their culture. Some respondents suggested art, theatre, and music as tools to educate young people about their political rights; others suggested that inter-cultural activities infused into civic education could build friendships that connect diverse populations. While culturally responsive activities make civic education more relevant, it is important to be mindful that some cultural norms create barriers to the participation of young women and youth with disabilities.

Remember, not all methods of engagement are accessible to and inclusive of everyone. Being aware of this, and anchoring activities with young leaders, CSO partners, and community and elected leaders can help ensure that engagement is equitable and inclusive. Indeed, rooting civic education efforts in community organizations and structures—such as youth clubs, cultural centers, and community places where young people gather and feel most safe and free to express themselves—is key to tailoring and implementing effective and sustainable programming.

Tip 1: Recognize Social Media as a Platform for Leadership

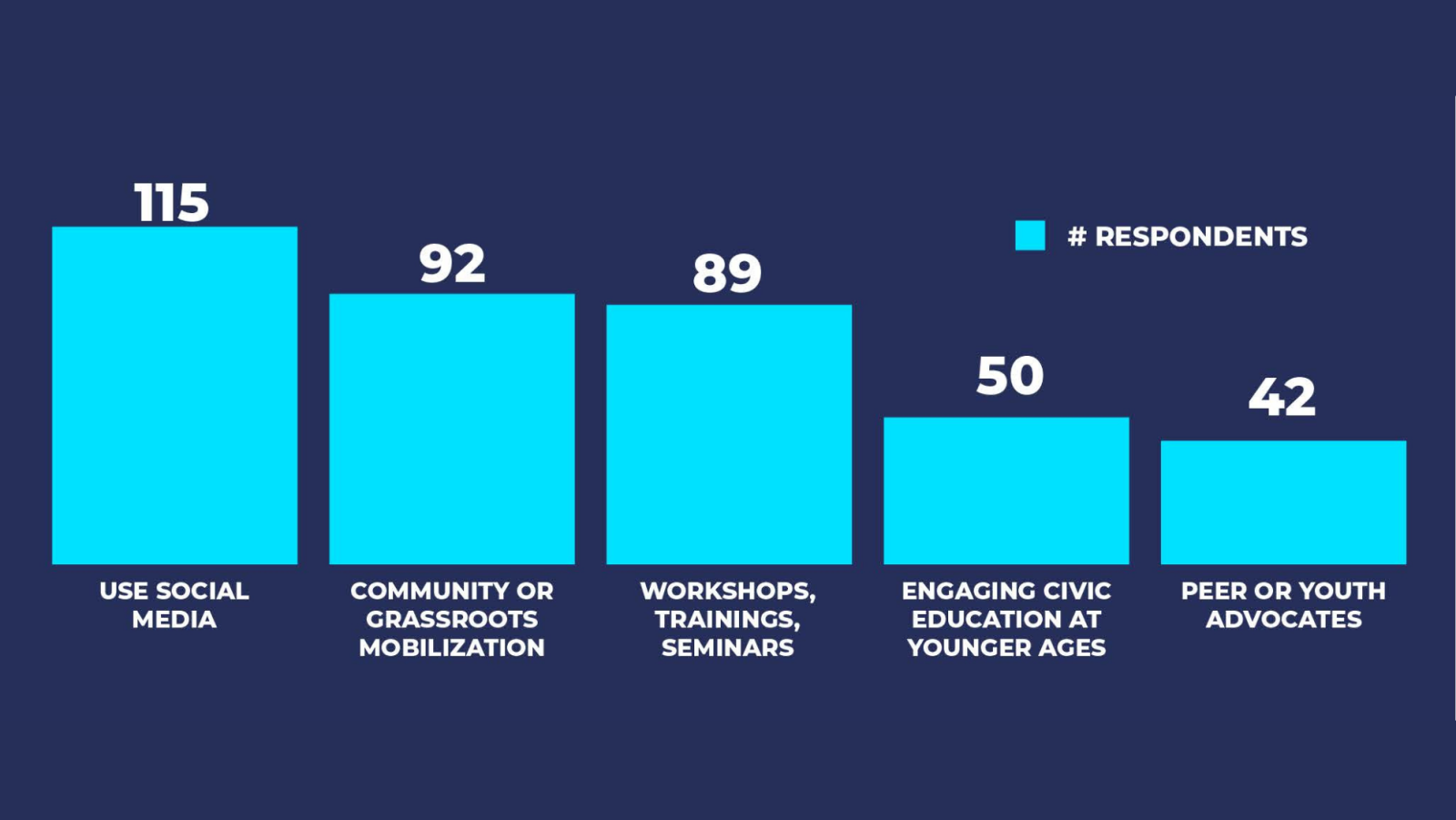

Young people leverage social media in multiple ways. These include organizing virtual town halls, conducting digital advocacy campaigns to raise awareness of issues they care about, and mobilizing election participation through voter education. Survey respondents confirmed that social media is the number one way that young people lead nonformal civic education in their communities. Interestingly, this was also true for 96 percent of young people who identified as living in rural areas. Social media was also the method that survey respondents recommended most often for engagement (see Figure 12).

Young people’s increased engagement in social media reflects their use of this platform as a valuable source of information. When asked to select the most effective method for conveying information, 45 percent of respondents across regions and age brackets, including women and urban and rural youth, selected social media. One focus group participant explained that this is because young people think social media is “the fastest and easiest way of disseminating information.”

and engage them.

Engage young people in the design and rollout of social media campaigns. Incorporate learning about leadership skills

in online spaces.

Tip 2: Apply a Mixed Media Approach

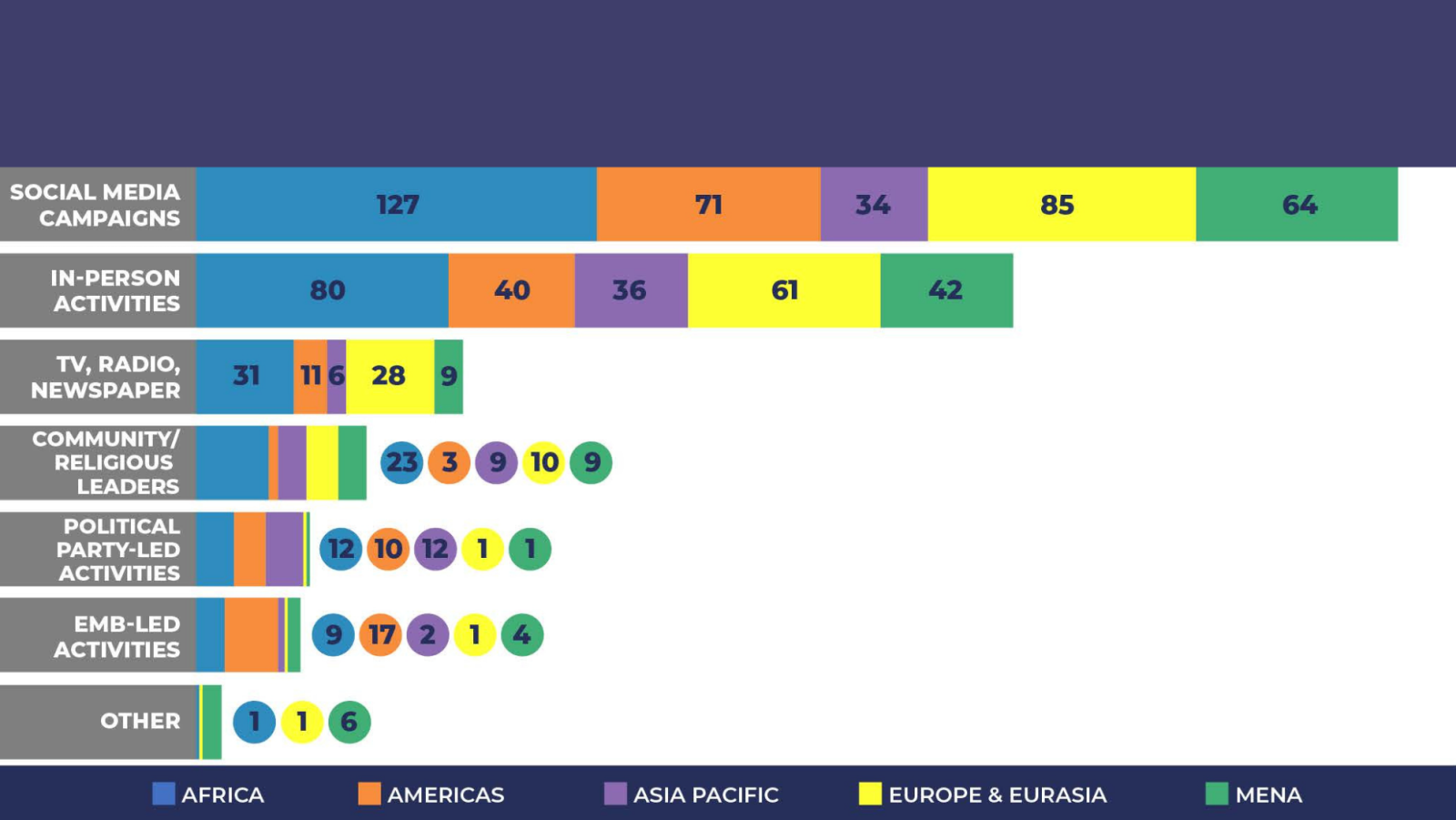

While young people use social media, the data show that other methods might be equally important. When asked the most effective method for conveying information, survey respondents chose social media and in-person interactive engagement as their top choices. The first choice among respondents who completed school up to eighth grade was in-person engagement rather than social media, which was the first choice for all other demographics. FGD participants preferred face-to-face engagement and interactive media because they allow for more human connections. Engaging young people through a mixed media approach—one that combines digital and social media with traditional media—could best engage young people across all demographics (see Figure 13).

The qualitative data further support the case for using a mixed media approach to nonformal civic education. Survey respondents explained that the most effective way to increase young people’s engagement in democratic processes is through social media, either in tandem with or followed by in-person approaches. Notably, through this nuance, young people are identifying ways to overcome the digital divide and challenges related to internet access and accessibility. Ensuring civic education efforts leverage multiple media approaches may more effectively engage diverse youth populations as they acknowledge that the digital divide is both a challenge and an opportunity.

If safe to do so, livestream events or radio shows on social media to maximize your reach.

Include traditional and digital media approaches in learning materials to bolster young people’s skills to engage in person and digitally.

Tip 3: Acknowledge Young People with Intersectional Identities

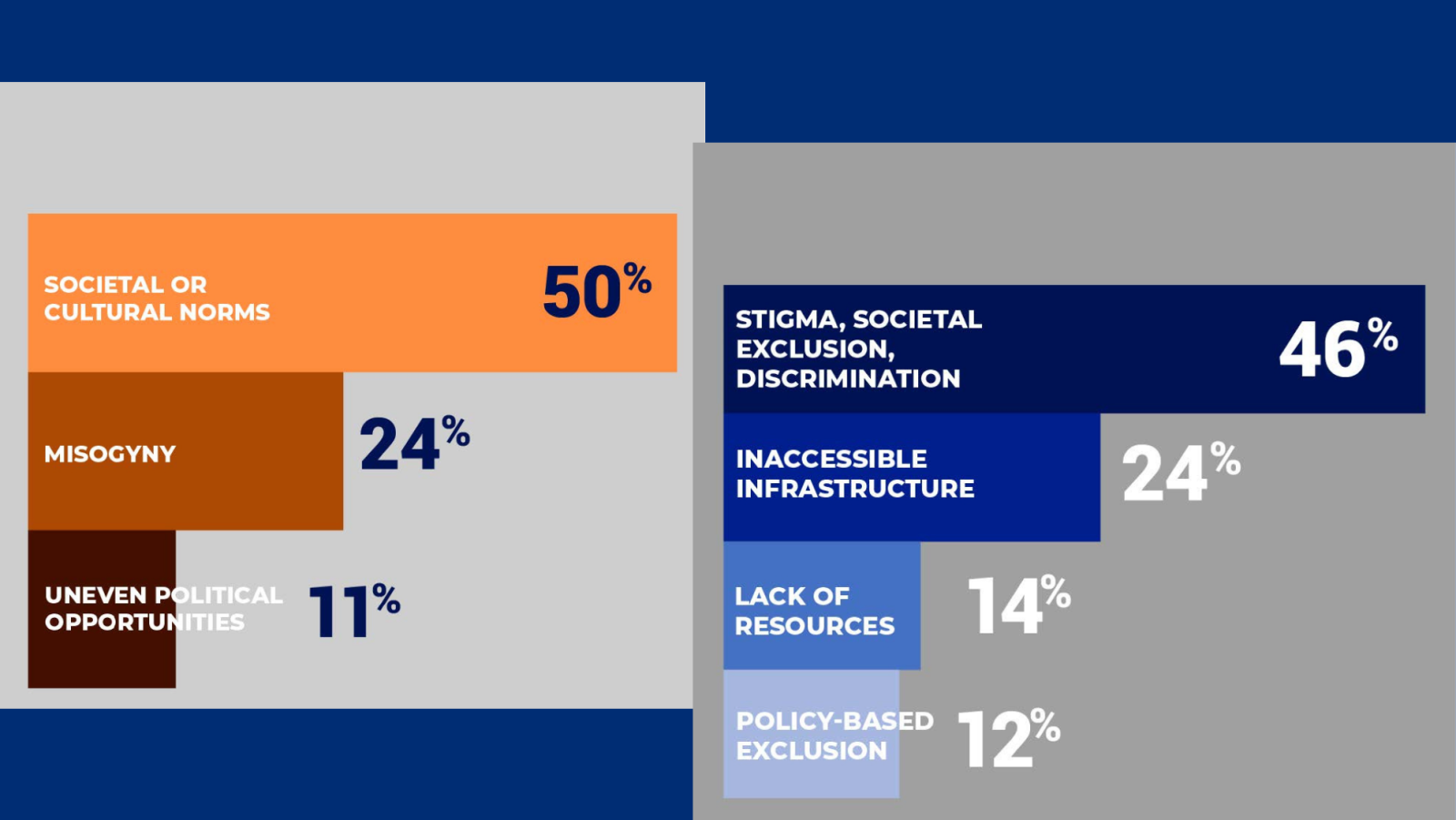

Marginalized populations, such as women, people with disabilities, ethnic or religious minorities, and Indigenous Peoples, often face barriers to political and civic participation. The survey data revealed that young people from marginalized populations feel the lack of equal opportunity acutely. This is particularly true for people with intersecting marginalized identities. Some respondents with intersecting identity markers, particularly young people with disabilities and young minority women, reported that they are prohibited by traditional customs or patriarchal practices from participating politically. One respondent shared that young women often face a “double burden,” as there is limited political space for both young people and women to participate. The survey also found that young people with disabilities face exclusion due to stigmatization, which further isolates them from decision-making processes (see Figures 14 and 15).

In practice, inclusion should be a culture in which all young people are engaged and diversity is celebrated. This can start by purposefully engaging young leaders with diverse backgrounds and intersectional identities in activities. Learning materials should reflect their experiences, be relevant to their identities, and made accessible for people with disabilities.

Apply an intersectional lens to program design to raise awareness of and tailor programming to the experiences of young people with intersecting identities to ensure accuracy, sensitivity, and representation.

Tip 4: Make Civic Education More Accessible

In addition to mainstreaming the intersectional identities of young people into programming approaches and honoring this diversity in democratic processes, practitioners should also make civic education available to and accessible for all learners. Accessibility goes beyond navigating physical barriers in institutional settings, such as schools and polling stations. Respondents cited economic conditions, a lack of education, and poor infrastructure, such as internet access, as challenges to engaging young people in rural areas. They also noted that the interests and engagement of young people will vary across geographical areas.

Focus group discussants noted that making the structure and format of civic education programming accessible is important to address the barriers that young people with diverse identities face as they enter public life. For in-person programming, accessibility measures can include holding activities on the ground floor of a building, inviting assistants of people with disabilities, offering transportation services, and providing child care. For online civic education efforts, this can include providing funds to top up phone credit and data, providing sign language interpretation or closed captions, and recording sessions. Whenever possible, invite program participants to inform the formats of initiatives based on their preferences.

ENGAGE

IFES’ award-winning Engaging a New Generation for Accessible Governance and Elections (ENGAGE) is a political leadership course for young people with disabilities. The course builds leadership skills and provides practical experience through networking, internships, and community action projects. ENGAGE addresses the ableism and ageism that young persons with disabilities often face when engaging in civic and political life and provides opportunities to increase knowledge and build skills for leadership in their communities.

Make sure activity locations enable all attendees to participate safely. Budget for reasonable accommodations and accessibility features for materials to ensure activities are accessible to all.

Case Study: Inclusive Digital Advocacy Toolkit

IFES created the Inclusive Digital Advocacy Toolkit to support diverse advocates to enhance their digital advocacy skills and in response to increased activism in digital spaces.18 The toolkit takes an intersectional approach, with particular attention to the unique experiences of people who identify with multiple marginalized groups, such as young people with disabilities or ethnic minority women. The toolkit also provides examples of ways that digital engagement can address barriers to meaningful participation. As of 2023, young leaders, including young people with disabilities, young Indigenous Peoples, and youth-led civil society stakeholders from 16 countries, have used the toolkit.

The Inclusive Digital Advocacy Toolkit showcases how advocates can leverage digital tools for advocacy and provides guidance for digitizing in-person events to share activities with a larger online audience. In addition to actionable strategies for online advocacy, the toolkit stresses the importance of online safety. Indeed, focus group discussants identified the need for digital literacy as a component of civic education to ensure the safety of young people in digital spaces. The toolkit has been shared with CSOs and global youth activists who use it to develop their own social media campaigns, support youth inclusion in disability rights campaigns, and expand the digital reach of their efforts and the effectiveness of their online content.

Case Study Tips

- Outlines steps to create a social media advocacy campaign.

- Follow the algorithm tips to maximize the reach of your campaign.

- Identifies ways to amplify in-person engagement through digital tools.

- Take a quiz to determine what type of advocate you are and find relevant advocacy tools to employ in your efforts.

- Includes real-world examples of diverse advocates from around the world.

- Map your digital environment and networks to ensure your campaigns are inclusive of diverse stakeholders.

- Provide guidance on how to make content more accessible.

- Apply inclusive communication strategies such as alt-text and adding captions to videos to reach and engage all users.

Tip 5: Engage Young People Under 18

Engaging people under the age of enfranchisement19, often 18, in civic education is critical to instill democratic norms, attitudes, and behaviors that will ensure lifelong civic and political participation.20 Survey respondents and FGD participants repeatedly made this point, stressing the importance of engaging children to create more sustained patterns of engagement in adult life. One focus group discussant noted how school government or youth parliament programs can build political behaviors. Respondents also mentioned secondary impacts—the spillover effect.21 For example, civic education for children can benefit others because children often talk about what they have learned with their families and friends; this secondary knowledge exchange has the potential to influence the behavior of those who have not participated directly in programming.

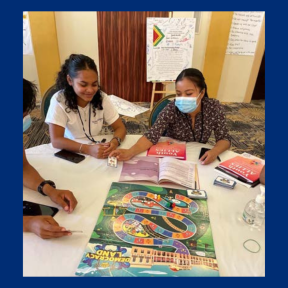

Survey respondents identified a need to move away from traditional learning structures such as formal school curricula and explore more interactive modalities, especially for younger learners. Using hand puppets, card games, trivia contests, or board games that merge entertainment with civic education is a fun way to bring friends and family into the learning process. Materials should be adapted to learning styles and age groups; they should use varied communication styles and age-appropriate text and images and should support cognitive development.

Youth ALLIES

The USAID-funded Youth Advocacy, Linkages, and Leadership in Elections and Society program trained Guyanese youth to use interactive civic education toolkits to mobilize their communities. The toolkits use board and card games to teach players about democracy, the branches of government, advocacy, and inclusive problem-solving. The games can be played with peers, families, and community members.

Provide opportunities for them to work and learn together.

Obtain consent from parents and caregivers and assent from learners under age 18 for their participation and use of their images or quotes. Add safeguarding mechanisms for the inclusion of young people under age 18 in programming scopes of work.

Tip 6: Incorporate Peer-to-Peer and Intergenerational Learning

Survey respondents identified engaging peer advocates through peer-to-peer learning as an effective and inclusive approach to civic education. They cited youth-led and -designed activities that invest in young people as advocates and educators as a sustainable approach to sharing information among communities (see box at left).22 Partnering with young people as trusted colleagues can help ensure that programming is relevant and can reach diverse groups of young people. For example, consider reaching out to youth clubs, associations, or networks. Establishing feedback loops for young people to share ideas for programming were mentioned as opportunities to engage more youth voices; these could look like focus group discussions, youth councils, or working groups.

Intergenerational learning opportunities are also important—not just to provide young people with mentors and insights from the lived experiences of adult peers, but also to dispel the stereotypes that adults may have of young people and to share important civic education information with them. Young people’s exposure to democratic concepts through youth-focused civic education programs can be shared with adults; young people’s leadership and expertise can support their families, friends, and community members in navigating civic and political spaces, such as new social media platforms or polling stations.

Democracy: From Theory to Practice

IFES Ukraine’s Democracy: From Theory to Practice university course incorporates nonformal civic education programming through the capstone requirement in which students work together on community action projects to solve problems in their communities.

Provide opportunities for young people to network and work together with their peers and older community members.

Tip 7: Include Civic Education Throughout the Electoral Cycle

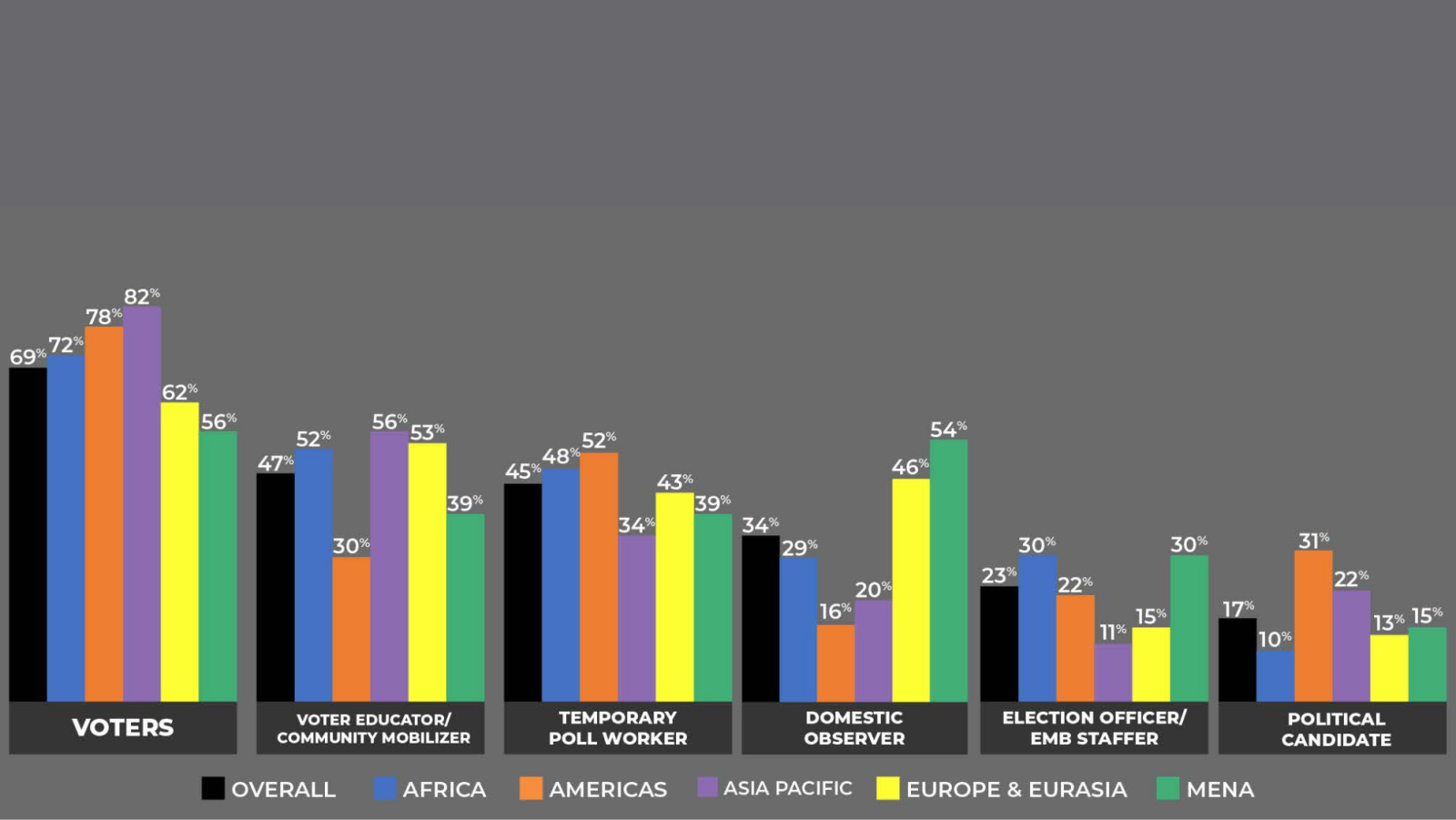

While respondents overwhelmingly expressed more interest in nonformal activities, they also noted the importance of youth participation in elections and the electoral cycle. Respondents identified the top three ways young people were observed participating in the electoral process—as voters, voter educators, and temporary poll workers (see Figure 16). Although observation of all behaviors varied by region, respondents in all regions observed young people voting the most. In Africa and the Asia-Pacific and Europe and Eurasia regions, an average of 54 percent of respondents observed young people acting as voter educators or community mobilizers. In the Americas region, 52 percent of respondents observed young people serving as poll workers.

Survey and FGD respondents identified activities that young people can lead and participate in throughout the electoral cycle. These include conducting voter registration drives and party registration during the pre-electoral phase; mobilizing first-time voters and observing elections during the electoral phase; and advocating for electoral reform efforts that reduce barriers for young voters in the post-electoral phase. They also observed that building relations with EMBs and electoral authorities can foster more opportunities for youth engagement across the electoral cycle.

Focus program design on each phase of the electoral cycle to strengthen young people’s engagement in the pre-electoral and post-electoral phases and to build sustained habits of participation.

Case Study: Kimpact Democracy Schools

In 2020, KDI started Kimpact Democracy Schools (KDS) to invest in young people and the democratic health of Nigeria. KDS offer meaningful opportunities for younger Nigerians to add to their democratic knowledge while building civic and political participation skills through interactive activities and civic learning experiences, which have nearly vanished in conventional schools in Nigeria. KDS provides safe spaces for young changemakers from different social and educational backgrounds who aspire to be active citizens and leaders and to learn and exchange ideas on democratic ideals and civic life.

KDS offer trainings and camps throughout the year for cohorts ages 10–17 and 18–35. While the younger cohorts learn about democracy and its role in Nigerian history, the older age bracket focuses on skill-building opportunities through leadership and peacebuilding initiatives. In just two years, KDS trained 615 young Nigerians on democracy and human rights, civic leadership, and community organizing using a learning-by-doing approach. Alumni are encouraged to continue to engage with their peers through the KDS Alumni Network. Many KDS alumni are now active in civic life, advocate for the implementation of pro-youth policies, and demand accountability from public officials.

Case Study Tips

- KDS engages young people ages 10 to 17 to instill leadership and democratic norms in their development process.

- The age 10–17 cohorts learn about democratic ideals by discussing Nigeria’s history of governance and interacting with guest speakers who hold key democratic roles.

- KDS alumni network allows for peer-to-peer and intergenerational learning and mentoring.

- KDS activities offer participants first-hand practicum opportunities, including internships and site visits with public officials, EMBs, and CSOs.

- KDS promotes continuous and systemic learning during all three phases of the electoral cycle.

- KDS teaches skills that enable young people to take post-election leadership to advocate for government accountability.

Citations

International Foundation for Electoral Systems, January 2022.

In 90 percent of countries, the voting age is 18. See: Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening, 2019.

Law and Atkinson, 2021.

Finkel, Ratway, and Sigal, 2022.

International Foundation for Electoral Systems. Democracy.