2.1 Overview of Strategic Framework

Once you have considered the rules governing political finance in your jurisdiction, you next need to develop a strategic framework. The strategic framework will connect the legal framework within which you operate to on-the-ground implementation of your activities. A solid strategic framework not only will give life to the legislation, but it will enable you to deliver your oversight role in a more professional, proactive and effective manner.

Political finance institutions come in various forms and structures which will impact on how you set your strategy. The approach outlined below contemplates an agency set up with a Chair and group of commissioners who, as a Board, set the institution’s overall policy. Of course, in other countries one individual may be responsible for all aspects of the institution with assistance provided by a senior executive team. For our discussion, we use the term ‘Board’ to mean the person or group of individuals who decide the overall strategic framework for the institution.

Your strategy will stem from future-focused conversations with the Board about what the main aim of the organisation should be over the next few years. Achieving a high level of compliance with the law is a common aim amongst political finance oversight institutions but it far from being the only one. Whatever the key aim is for your organisation, it will require a clear vision for the future – a powerful and succinct statement of how you want the world to be, with a set of medium to long term objectives you believe will deliver that vision.

Your strategy will also include an indication of the methods and tactics you will employ to achieve your goal. However, your strategy should be aspirational rather than operational. For example, you may include references to education and stakeholder engagement as methods and tactics to achieve a high level of compliance.

A written strategy is essential. But good planners will also talk about strategy as a constant activity – something dynamic you are always doing as you sense new changes in your environment and work out ways in which your organisation can respond to them. Having an overall strategy and vision to guide you is extremely important, but your strategic mindset shouldn’t end on the day of publication. Strategy is a way of thinking about shaping the future, every day – it’s not just a document.

What is a strategic framework?

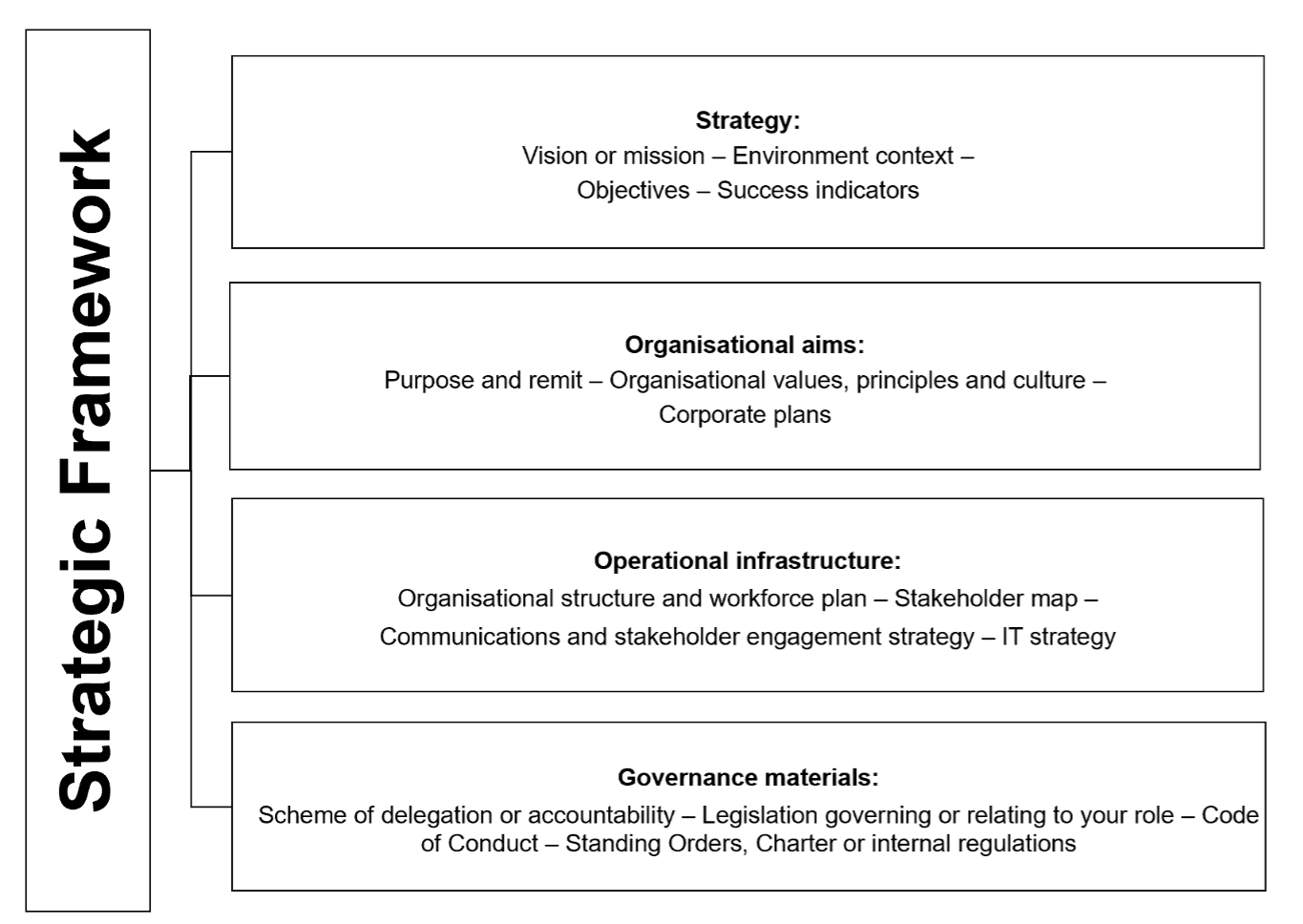

A strategic framework captures, in one place, your organisation’s strategy, aims, activities and ways of working. It sets out the architecture within which your oversight institution will operate and gives a blueprint for the successful delivery of your political finance aims.

As well as core elements such as your organisation’s purpose, your framework may include an articulation of the legislative and governance framework within which you operate, and a map of your operating environment, stakeholders, and drivers. It should also describe how you are resourced, and how you measure progress and success.

Why is it important to have a strategic framework in place?

It is a key tool that will put you in the driving seat.

It is an empowering tool, when used well, and provides some great communication assets. It also is essential for transparency and reporting purposes. Transparency is central to most political finance regimes and as the oversight institution, you are uniquely well positioned to model transparency and accountability.

Capturing a clear expression of your organisation’s purpose, vision and positioning will help you to plan more effectively, which in turn will help you to deliver benefits. Your framework will also provide guidance about how you run your organisation.

A golden thread should run through your framework. Your purpose and vision should inform your aims, your values, and your decision-making, so that these are aligned. This will greatly increase the likelihood of your efforts leading to success as an effective political finance oversight institution, and your staff seeing a clear link between their work and the overall vision.

Your strategic framework should not spend its life sitting somewhere in splendid isolation. It should be a ‘go to’ resource, consulted frequently, and updated regularly.

How to develop a strategic framework

There is no single approach to developing a strategic framework. Each organisation has its own starting point, its own culture and frame of reference, and its own preferences.

Some organisations choose to create their strategic framework in a single document, summarising down or referencing other documents. Others treat the framework as a suite of multiple separate documents, with an over-arching contents page and executive summary, kept in one folder or location. This is a matter of choice. If you opt for the summary document method, make sure you have a process in place for reviewing and if necessary, updating the summary document whenever related documents are updated.

The following diagram shows the elements that make up a strategic framework which are discussed below:

2.1.1. Components of a strategy

2.1.1.1. Vision or mission

Some organisations have an overall ‘mission statement’ or ‘strapline’ that describes their purpose in an accessible and pithy sentence. This may exist over and above the current strategy – it may be a permanent feature on letterheads, for example.

Other organisations use the words ‘vision’ and ‘mission’ interchangeably, meaning much the same thing – an aspirational statement encapsulating the difference you hope to make in the world over the next few years.

Others again have both a vision and a mission statement. In these cases, the vision statement is the aspirational statement about the desired future state, while the mission statement is a one-sentence expression of how (in general) your unique organisation endeavours to make a difference in the world. A mission statement may therefore relate closely to your organisational purpose.

For more about developing a vision or mission statement as part of a strategy, see the section on planning.

For examples of vision and mission statements, see Examples of vision and mission statements.pdf.

2.1.1.2 Operational environment

Any organisation’s work has a wider context. An environment analysis should be conducted periodically, especially when formulating a new strategy. It may be useful at other times too, for instance if there are major changes in your operating environment (e.g., legislative proposals to change the law), or if there are future ‘known unknowns’ (e.g. an emerging change in campaign advertising strategies) and you need to do some horizon scanning to enable you to do some scenario planning or risk management.

There are two main types of environment analysis – PESTLE and SWOT.

A PESTLE environment analysis looks outwards from the organisation, assessing the political, economic and social and other external factors all around you.

A SWOT analysis is more inward looking and helps you to gauge your organisation’s current strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

It is a good idea to conduct an environmental analysis at regular intervals. This will ensure that you remain forward-looking and relevant, make the most of your opportunities, and take risks in a calculated way.

For an example of environmental analysis tool, see Environmental analysis tool.pdf.

For a blank template for an environmental analysis tool, see Environmental analysis tool - blank template.pdf.

2.1.1.3 Objectives

Your medium to long term objectives in implementing your political finance mandate will stem from strategic thinking about your future operating environment, key drivers and likely politico-social developments in your sphere of influence. Starting from the overall vision, what will it take to make that vision a reality? What will be the main areas of focus and the changes that need to be brought about?

These objectives will form a key part of your strategy - you should set no more than six high level objectives that you believe will collectively lead to the realisation of your vision by the end of the strategic period you have set. For example, if your vision is to achieve high levels of compliance with the political finance legislation, your medium to long term objectives might include developing a range of advisory services and training initiatives for the regulated community. Similarly, if your vision centres on ensuring transparency of political party funding, your medium to long term objectives might include the development of an electronic filing and reporting system.

At other levels of planning, you will turn these long term objectives into a series of much more detailed and shorter term plans. But in the strategy, you are setting out a dream of a better future, with a broad indication of how you will achieve it. This is not the place for the details. So, in the examples given, the detail of the advisory services and content of training initiatives would not be delineated in your strategy, nor would the type and scope of the electronic database be specified.

For oversight institutions that have been in existence for some time, the strategic thinking process may lead to changes in vision and objectives. If so, you will want to consider whether there are activities that you might stop doing and the consequential implications for staff, stakeholders and other strands of your work.

Because you are not going to include a great deal of operational detail in your published strategy, it’s important to reality-check your objectives before publication. This means leaving enough time for your staff to discuss how each objective could be delivered within the time and resources available, and to share this information with the Board, formally or informally. This ‘unpacking’ conversation will give your staff a better understanding of the new strategy while it is still in development, it will give your Board insight and assurance, and it will provide a good foundation for the more detailed operational planning that will flow from the finalisation of your strategy.

Like all objectives, they should be SMART – specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and timely (see How to write SMART objectives.pdf).

2.1.1.4 Success indicators

When setting a strategy, it’s important that the Board develops a shared understanding of what they think success as a political finance institution will look like, and to include information about this in the strategy itself. This is a way of sharing your idea of success and making yourselves accountable against it. How will you and others know when you have succeeded? Are there some measures you could set or milestones you could describe that would enable you to demonstrate progress along the way? What will be different when you have achieved each objective, and what will be different when your whole vision has been realised?

Success indicators should ideally be quantitative – but it’s important to remember that not everything that can be measured is meaningful, and not everything that’s meaningful can be measured. It may make sense for some of your objectives to include success indicators that are qualitative, where the data will be descriptive and conceptual, rather than solely numerical.

For more information about setting key performance indicators (KPIs), please see the separate section on performance management.

For information about benefits realisation, please see the separate section on project management.

2.1.1.5 Developing a strategy

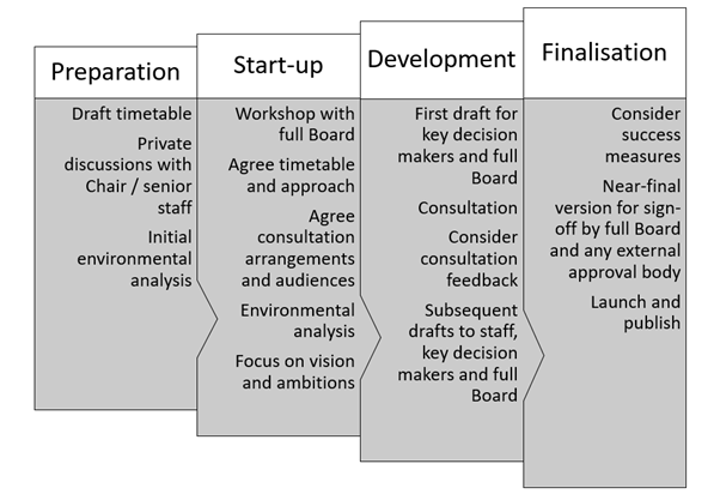

Strategy development requires time and the space to think big. There needs to be adequate opportunity for group discussion at the most senior levels of the organisation – discussions that allow for horizon-scanning rather than a focus on detail. Time is also needed to consult and seek input from the heads of operational units. Before you embark on the substantive work, it is advisable to have clarity on the process – who will facilitate group discussions, where should workshops be held, who will formulate the initial draft of the strategy and what stakeholder consultation will be undertaken, etc. The following chart summarises the various stages of the process.

2.1.2 Organisational aims

The purpose of a political finance oversight institution may seem obvious, namely to oversee the rules governing political finance. Whilst this is true, your organisation will benefit greatly from thinking about its core values or ethos and the principles that will guide you in how you perform your work. Will you want to adopt a culture of continuous improvement for your organisation? Do you want to try to prevent violations from occurring or simply enforce the rules stringently? The decisions you make about such matters are important; they will help inform which activities you undertake and how you approach them.

2.1.2.1 Purpose and remit

Your organisation’s purpose should explain why you exist. Specific legislation (or the country’s Constitution) generally sets out the political finance oversight body’s purpose. In many countries, however, the political finance remit is just one of many conferred upon a particular organisation (e.g. an election management body, an anti-corruption agency or a state audit office) and the political finance oversight role may not be sharply defined. Even where documents do address this role, they may use lengthy phrases and jargon, so it is a good idea to have a pithy, easy to understand, statement of purpose that makes clear what the core reason is for your existence. This can help you to stay focused, as well as providing clarity for your staff and external stakeholders.

As well as a short statement of your purpose you should also include accompanying text about why and how your organisation was formed in the first place, and what needs it meets.

It’s also worth recording any statutory obligations and whether there are limits on or exclusions in your remit (e.g. you may regulate only the finances of political parties but not those of candidates), whether there are areas of overlap or interface with other bodies (perhaps the State Audit office oversees public funding), or whether you are working to expand your role. Some commentary on such matters may be helpful, especially if you sometimes find that others have misapprehensions about your organisation’s role and remit.

For hints and tips on how to develop your organization’s purpose and remit, see Developing your organisation’s purpose and remit – hints and tips.pdf.

For an example of statement of purpose/ remit, see Example of statement of purpose - remit.pdf.

2.1.2.2 Organisational values, principles and culture

You may already have documents such as a Staff Charter, or a set of agreed ‘ways of working’ and values. This will set out the principles and values that are seen as important within your organisation, and will provide a guide for institutional decision-making and staff’s behaviour. Having a written statement of ‘what’s important to us’ and ‘the way we do things around here’ can help everybody to perform at their best.

This is particularly true for political finance oversight institutions who, in essence, are the referee for the financing of electoral contests that determine who will govern the country. It is not surprising that the principles of impartiality, objectiveness, independence and transparency often appear in oversight institutions’ statements of values, principle and culture.

It is a good idea to have regular conversations with your staff about your principles and values, to ensure that everyone understands what is expected of them and has a chance to air new suggestions. Creating a values statement is often led by your Human Resources team, but it’s important that it is seen as belonging to everyone. This can be achieved by engaging with staff during its development.

Some hints and tips for the creation of your organisational values, principles and culture:

- Consult and communicate with staff about your values, principles and culture – only they can bring it to life.

- It’s fine for your HR team leader to take the lead on developing a values and culture document, so long as they ensure you have buy-in – from everyone – for the end result. To achieve this they will need help from other organisational team leaders to generate the content, and to consult and engage with staff effectively.

- It’s worth thinking of ways of recognising and rewarding those who best model your organisational values, principles and culture.

For examples of organizational values, principles and culture, see Examples of organizational values, principles and culture.pdf.

The chosen values and principles should reflect not just how you work together internally as a team, but also the way you work with other organisations and stakeholders to achieve the best possible outcomes.

2.1.2.3 Corporate plans

Corporate plans will set out in more detail what you are planning to do to realise your organisational vision and to deliver your purpose. Your corporate and other plans are led by your strategy, but will be more operational in nature, since they will set out the activities, projects and timelines for individual pieces of work. See the section of this toolkit dedicated to planning.

2.1.3 Operational infrastructure

Your organisation will have a particular shape, size and composition. It will have a structure that suits your functional needs. This doesn’t only consist of your workforce, however, but also your IT infrastructure, and your key external relationships. These things – your staffing structure, your stakeholder relationships, and your IT system – form the central spine of your capability to operate. You may also have particular policies and sub-strategies relating to them, and other documents too such as an ‘organogram’ (a diagram showing how your departments are structured) and a stakeholder map. It is worth drawing these elements together into a cohesive whole in your strategic framework – they are central to your organisation running smoothly.

2.1.3.1 Organisational structure and workforce plan

Small or large, your organisation will have a structure – be that a single office or a network of regional locations, or an organisation with multiple functions. It is useful to have a diagram showing the structure and divisions. If your organisation is complex or disseminated, you may wish to go further in this section and discuss why your organisation has taken the shape it has, or how the structure serves your organisational purpose.

Your workforce or staffing plan will set out how you intend to resource your delivery in the medium to long term. As such, it should be reviewed whenever you begin a major round of planning, or when you encounter change. Your workforce plan may be simple and focus mainly on retaining the staff you need in order to fulfil your role; or it may be more complex, setting out how you plan to re-shape your staffing structure over time, in order to meet new needs, such as changes in political finance legislation or adapt to new technologies (e.g., e-filing databases).

For political finance institutions, the workload can be cyclical, peaking in the run up to elections with a second peak around the time campaign finance reports are submitted. The workforce plan should address how you intend to address these known peaks.

Some hints and tips on how to develop your organisational structure and workforce plan:

- Your organisation structure will be more or less complex depending on the size of your organisation, the number of its functions and the number of offices/branches you have.

- It can be a very simple diagram showing only departments, or you may choose to show more of the hierarchical detail. This will depend on who needs to see it, and how you are going to use it.

- Your workforce plan should set out how you will match skills and capacity to your ambitions. It will also address future changes (e.g. in your operating environment or in society) that will have an impact on your human resource needs over time

For examples of organograms and workforce plans, see Examples of organograms and workforce plans.pdf.

2.1.3.2. Stakeholder map

You are likely to maintain a range of collaborative and information-sharing relationships with other bodies. Some of these will be important allies in reaching your strategic vision, such as prosecutorial authorities who will take forward cases of wrongdoing or governmental departments that can provide you with relevant information about donors to ensure the legality of contributions.

In some cases, you may have formal written agreements between you about ways of working on certain matters (e.g., Memoranda of Understanding). There may even be contractual arrangements between organisations, if you, or they, perform a service on the other’s behalf.

It is worthwhile mapping out your various stakeholders, to assess their level of interest in and influence over your work. Your stakeholder map should be reviewed regularly, since the landscape in which you operate will change over time, and new stakeholder groups may emerge – for instance new civil society groups who focus on anti-corruption and political finance. Also, some organisations are now involving social media ‘influencers’ with an interest in relevant subjects in policy discussions - see the section on Stakeholder engagement.

Some hints and tips regarding stakeholder mapping:

- Most of your stakeholders will be organisations or individuals with whom you want to have a productive relationship.

- You may also want to develop a stakeholder relationship with those who may sometimes be critics (for example media organisations, political entities)

- You may want to categorise your stakeholder according to the amount of interest and influence they have in your area. This will help you to prioritise which stakeholder to invest the most energy in.

- It is worth reviewing your stakeholder map once a year, or whenever your external landscape has changed. This will help you to ensure that you do not miss new opportunities, or over or under-estimate the influence of particular stakeholders, since these can change over time

2.1.3.3 Communications and stakeholder engagement strategy

You may have a communications and/or stakeholder engagement strategy setting out how you will use your channels, or involve your stakeholders, in delivering certain aspects of your work. Some organisations go further and may also have a distinct social media strategy (for example). It’s important that this links to, and serves, your overall strategy.

Communications and stakeholder engagement are often combined into a single strategy, or may be separate. A communications strategy will focus on how you will promote your content to your target audiences, so that your messages land effectively with the right people and have the most effective impact and influence. The communications strategy will set out what channels you plan to use for various types of communication – for example your website, press releases, social media, or publications.

A stakeholder engagement strategy will focus on identifying the key groups (and possibly individuals) that you would like to listen to, and perhaps also to work with on relevant issues. For political finance oversight bodies, these groups often include political parties, candidates, parliamentary committees, journalists, and other state institutions such as the prosecution authority, ministry of finance etc. The engagement strategy will set out how you plan to interact with them, gain useful feedback from them, and make the experience a positive one so that they will engage with you again in the future. Some extremely useful relationships can be formed, and external intelligence and input gained, in this way.

Some hints and tips on how to develop your communications and engagement strategy:

- Your communications strategy should address the key messages and content you plan to promote, the channels you will use, and the frequency with which you will use those channels

- Your engagement strategy will focus on who you want to listen to and interact with, how and when you will engage with them, and what methods you will use (meetings, focus groups, consultations)

- All good relationships have mutual benefit, and are worth investing time and effort to maintain. It’s worth periodically reassessing your relationships to ensure that this remains true

- Any external ‘user groups’ you engage with will have a membership that is not under your control, and that membership may become out of date or out of touch over time. That’s another good reason to revisit your stakeholder map and your communications and engagement strategy periodically, to ensure that the feedback you receive from such groups remains relevant and useful

2.1.3.4 IT strategy

Your organisation IT strategy should cover your IT assets, the management of turnover in IT equipment, any planned system work or expansion of IT equipment (e.g. growth in number of users) and how you manage cyber-risks. Within the context of your political finance role, there has been significant movement internationally towards e-filing database systems for submission of finance reports and an increase in digital publication of finance data. See the sections on Publication of data, actions and decisions and on Preparing reporting.

Allied to your IT strategy, you should also have a business continuity plan, for use in emergencies. Key personnel should keep a paper copy of your business continuity plan off premises (e.g., at home) in case you need to refer to it at a time when your office is unavailable or your IT systems are down. Examples would include a fire, flood, major power outage, earthquake or another major incident involving the emergency services. The business continuity plan should be tested occasionally so that you can be sure contact details are up to date, and to familiarise staff with the procedure in case there were a real business continuity event.

2.1.4 Governance materials

Your governance materials will set out the rules and structures and processes you adhere to when you make decisions and take action. Your decisions and actions on matters that are within your remit need to be taken in a legitimate and legally defensible way. You need to be thoroughly conversant with your governance framework, and to encourage awareness among your staff of what ‘the right way of doing things’ is. Good governance makes good decisions more likely, and expensive legal challenges less likely - or at least, less likely to succeed.

2.1.4.1 Scheme of delegation or accountability

This will set out who you are accountable to, and what you are accountable for. Schemes of delegation and accountability can be very detailed, and you may wish to consider including only a top-level version in your strategic framework (with a more detailed version used for internal, operational purposes). The scheme should explain who has the authority to make different types of decisions, e.g. who has authority to initiate an investigation, to determine whether a violation has been committed or to grant a political party an extension of time to file a financial report. If another body is ultimately accountable for some or all aspects of your work (e.g. parliamentary committee, governmental department, national audit office, etc), the scheme of delegation will make this clear and describe your external accountability arrangements with them as well as your internal decision-making apparatus.

If you have any powers that are set out in law, your scheme of delegation may also describe how you manage and delegate the delivery of such powers internally, for example through a committee.

Some hints and tips on how to develop your scheme of delegation or accountability:

- Your overall scheme of delegation should be clear from the time your organisation is set up – it may be in statute, be decreed by Government or be set out in an instrument that confers on you a certain remit and perhaps certain powers.

- Your scheme should specify who you are accountable to (or state that you are a fully independent body). It should also state how you account to them, for instance through regular reporting and meetings.

- It should also specify any limits on your remit and decision-making powers, for instance matters that need to be referred elsewhere and are excluded from your remit, or decisions that must be made by those who have been democratically elected (e.g. Parliament).

- It should describe your internal decision-making structure and make clear which individuals or entities are responsible for different types of decision.

- This may include a description of how you delegate certain powers internally, for example through a committee.

For an example of a scheme of delegation, seee part 4 in the Corporate Governance Framework of the UK Electoral Commission.

2.1.4.2 Legislation governing or relating to your role

Most political finance oversight institutions are statutory creations and have specific legislation that delineates their functions and roles. In addition, other pieces of legislation are likely to be relevant to your organisation’s field of operation, so it’s a good idea to list them. Two common examples are Data Protection Laws and Codes of Administrative Procedure.

2.1.4.3 Code of conduct

Your code of conduct will address matters such as workplace behaviour, ethical principles and values (reflecting those in your Staff Charter, if you have one, or in your values statement), confidentiality and dealing with conflicts of interests. It should provide guidance, and be given to people when they begin a role – they should sign it to indicate that they have read and accepted it.

You may have one code of conduct for staff and another for Commission members, external experts, contractors or stakeholders who are working with you on a project or providing advice. If there is more than one code of conduct, it should be made clear which groups of people each one applies to. Moreover, it is important to review Codes of Conduct from time to time to ensure they remain fit for purpose. The review should encompass all Codes of Conduct to ensure consistency and that the ‘golden thread’ isn’t broken.

The provisions dealing with conflicts of interests is particularly important in the context of political finance oversight as it goes to the very heart of the institution’s impartiality and independence.

Some hints and tips on how to develop a code of conduct:

A typical code of conduct will cover:

- Ethical principles and corporate values to be adhered to

- Clear accountability guidelines, for example on appropriate use of information, confidentiality, and avoiding or declaring conflicts of interest

- Standards of conduct, such as appropriate email usage and conflicts of interest

- The consequences of failing to live up to the standards set out

- Any relevant legal or contractual liabilities that may apply in certain roles.

You may need more than one code of conduct (e.g. one for staff and another for non-execs or expert advisers).

Here are examples of codes of conduct of political finance oversight institutions (Examples of codes of conduct.pdf).

2.1.4.4 Standing orders, charter or internal regulations (the rules within which you operate and make decisions)

Standing orders (also sometimes called a Charter, internal regulations or House Rules) set out the procedures that apply within your organisation. Areas covered may include the governance of your Board and committees, the procedures you follow during meetings (for example, how and when to take a vote), your administration and procurement procedures, and the various ways in which management decisions can be taken, for example about financial matters or changes of policy.

Some hints and tips on how to develop standing orders or charter:

- Your standing orders should set out, in detail, how you operate and make decisions.

- Standing orders may include:

- Instruments of delegation

- A list of any powers or decisions that cannot be delegated

- Powers of the Chair and Chief Executive; or Commissioner and Executive Director; etc

- Rules to be followed in order to amend Standing Orders

- Procedures governing formal decision-making meetings

- Committee terms of reference, membership and quorums

- How and when a formal vote will be taken

The standing orders of the UK Electoral Commission are included as Annex A in their Corporate Governance Framework.

2.1.4.5. The terms of reference of your Board and its committees

Terms of reference set out the role and constitution (structure) of a Board, Committee or Working Group. The terms of reference will include a brief description of the group’s remit, its authority and its composition. A quorum will also be listed – this is the minimum number of attendees required to make a decision. The terms of reference may also establish other rules such as who else can attend the group’s meetings (for example observers or staff).

Many organisations publish their terms of reference, in the interests of transparency about their decision-making apparatus.

Some hints and tips on how to develop terms of reference for your Board and its committees:

- Your formal committees’ terms of reference should be contained within Standing Orders (or a similar instrument of governance).

- Informal or staff boards and committees should also have terms of reference, to ensure clarity of purpose and an appropriate membership.

- It’s important that terms of reference clearly specify the role of the Committee and state clearly what matters have been delegated to it, and by whom.

- The terms of reference should also include the composition of the committee, the length of a term of office, and the nature of the membership (e.g. a mixture of professionals with specific knowledge sets and ‘lay’ members). It may also list people who are entitled to observe the proceedings, without participating in debate or decision-making, and anyone who needs to be present in an expert capacity to provide advice (for instance legal or constitutional advice).

- The terms of reference should specify a quorum – the minimum number of members who need to be present to make a decision.

The Terms of Reference of the Audit Committee and of the Remuneration and Human Resources Committees of the UK Electoral Commission are included as Annex G and H in their Corporate Governance Framework.